Exhibition Catalog

Chinese American Museum, 2007

Below: front and back covers

(click image to enlarge)

Recently I purchased a copy of the 2007 Chinese American Museum exhibition catalog, Sunshine and Shadow: In Search of Jake Lee. I expected to read Lee’s biography but there were only a few details about his life. On pages eleven and twelve it said:

Most biographies begin with a date and place of birth, but Jake Lee’s story begins with a question mark. Lee informed his friends, colleagues, and students that he born in 1915 in Monterey, California. When he died in 1991, his death certificate and memorial service program confirmed the date of birth, but provided new information as to the location: Lee was born in Guangzhou, China.Pages eighteen and nineteen had a few more details.

A photograph of Lee as a toddler (left) in California indicates that he left China at a very young age. He grew up in Monterey, where many of the small Chinese American community relied on fishing for their livelihood….Lee’s father ran a grocery-delivery business; he loaded a truck in Monterey with produce, canned goods, and dried fish, and sold to the Chinese communities along the Sacramento Delta.

Much of the mystery surrounding Lee continues to prevail. None of Lee’s family members could be located during this effort to uncover the basic facts of his life. They are only revealed through indirect reference: the return address of a sister in living in San Antonio, Texas; the name of a brother in Castro Valley, California; the names of his parents, Dea Sing and Chin Shee, on Lee’s death certificate; an early photograph that presumably shows Lee’s family. Those who knew him recall that Lee did not mention his family….With this information, I searched Ancstry.com. The U.S. Federal Census yielded one hit: the 1920 census enumerated January 7.

The catalog said Lee’s parents were Dea Sing and Chin Shee. Sing and Shee are not names but titles for mister and miss. The family name was Dea. The census recorded the Dea family at 324 Washington Street, Monterey, California. The catalog said Lee grew up in Monterey.

The enumerator’s handwriting makes the name on line 64 look like “Dea Ding”, but I believe it says Dea Sing. His occupation was the grocery trade which matches the catalog description. Dea’s wife was recorded as “Dea Chin”, so part of her name matches the catalog and death certificate names.

The first child, Hong D., was five years old and born in China. Lee was born October 23, 1915 in China, according to the California Death Index. This information matches the census data. Lee’s birth name was Hong D. Dea.

Hong’s younger siblings were a girl and boy, both born in California. The catalog said Lee had a sister and brother. Members of the Dea family emigrated to the United States after Hong’s birth.

How did Hong D. Dea become Jake Lee? According to the census, there were six lodgers in the Dea household, five of them had the Lee surname. Perhaps this group was the source for the name. The reason for the change is a mystery but I have a theory to share later on.

The Dea family has not been found in subsequent censuses.

The catalog said Lee was born in Guangzhou, China. The Dea surname (also my family name a few generations ago) suggests that the family was from the Sze Yup area west of Guangzhou.

My research turned to passenger lists. Ancestry.com recorded a two-year old boy, Hung Dock Dea, who traveled with his mother, Chin Shee, 41, and sister, May Gue, 16. They sailed on the S.S. Siberia which departed Hong Kong, May 16, 1914, and arrived in San Francisco, June 13, 1914. The trio had resided in Hoi Ping (see below, column ten), known today as Kaiping (in Mandarin) which is part of Sze Yup. Column eleven recorded the name of a relative or friend, Sun Yuen Shing whose address was 36 Wing Lok Street, Hong Kong. (I visited Hong Kong in 2014 and learned that Wing Lok Street and nearby Bonham Strand housed scores of herb shops. Today, a street sign says Bonham Strand is also known as “Ginseng and Bird’s Nest Street”.) Monterey, California was their final destination as noted in column twelve.

The enumerator’s handwriting makes the name on line 64 look like “Dea Ding”, but I believe it says Dea Sing. His occupation was the grocery trade which matches the catalog description. Dea’s wife was recorded as “Dea Chin”, so part of her name matches the catalog and death certificate names.

The first child, Hong D., was five years old and born in China. Lee was born October 23, 1915 in China, according to the California Death Index. This information matches the census data. Lee’s birth name was Hong D. Dea.

Hong’s younger siblings were a girl and boy, both born in California. The catalog said Lee had a sister and brother. Members of the Dea family emigrated to the United States after Hong’s birth.

How did Hong D. Dea become Jake Lee? According to the census, there were six lodgers in the Dea household, five of them had the Lee surname. Perhaps this group was the source for the name. The reason for the change is a mystery but I have a theory to share later on.

The Dea family has not been found in subsequent censuses.

The catalog said Lee was born in Guangzhou, China. The Dea surname (also my family name a few generations ago) suggests that the family was from the Sze Yup area west of Guangzhou.

My research turned to passenger lists. Ancestry.com recorded a two-year old boy, Hung Dock Dea, who traveled with his mother, Chin Shee, 41, and sister, May Gue, 16. They sailed on the S.S. Siberia which departed Hong Kong, May 16, 1914, and arrived in San Francisco, June 13, 1914. The trio had resided in Hoi Ping (see below, column ten), known today as Kaiping (in Mandarin) which is part of Sze Yup. Column eleven recorded the name of a relative or friend, Sun Yuen Shing whose address was 36 Wing Lok Street, Hong Kong. (I visited Hong Kong in 2014 and learned that Wing Lok Street and nearby Bonham Strand housed scores of herb shops. Today, a street sign says Bonham Strand is also known as “Ginseng and Bird’s Nest Street”.) Monterey, California was their final destination as noted in column twelve.

The travel expenses were paid by “Dea Singh” of Monterey in column 18. The last column said the trio were born in “Hom Bin”, a village in Hoi Ping.

The boy’s name, Hung Dock Dea, is very close to Hong D. Dea of the census. Their age differs by three years and both were born in China. The parents’ names in the passenger list and census are almost identical. Hung Dock Dea was Hong D. Dea who became Jake Lee.

Lee emigrated to the United States, so there would have been Chinese Exclusion Act case files on him, his parents and older sister. His parents’s testimony would have Lee’s birth information. The image of the passenger disposition list, below, has ticket numbers for the trio, 7-1, 7-2 and 7-3. Often the ticket number was part of the Chinese Exclusion Act case file number. In the upper left-hand corner is the number 13468.

On October 30, 2016, I emailed the National Archives branch in San Bruno, California, and requested information on the Dea family files. Archivist Ingi House replied on November 9 and gave the number of pages in each file with the file number in parenthesis.

Dea Singh (12017/48126) – 80 pages

Chin Shee (13486/7-2) – 41 pages

Dea May Gue (13486/7-1) – 34 pages

Dea Hung Dock (13486/7-3) – 35 pages

I wrote back on November 12 and requested copies of the interviews and documents with photographs. Ingi sent the new page totals.

Dea Singh – 18 pages

Chin Shee – 15 pages

Dea May Gue – 13 pages

Dea Hung Dock – 3 pages

I ordered these pages. After the payment was processed, scans of the interviews and other documents were emailed November 21.

The earliest interview for “Dea Singh” is dated November 1[?], 1899 and his name was “Dea Sing”. Twenty-five-year-old Dea, an only child, said he was born in San Francisco, California, at 622 Dupont Street. His father, Dea Wai Yick, died in 1896 in “Hoy Ping district, Pin Yuen village”. His living mother, Miss Wong, resided in the same village. Dea answered questions about relatives and the village.

|

| Page one of four |

Dea Sing traveled to China in 1910 and returned in 1912. On the document below, Dea gave the names and birth dates of his children. The closest match to Dea Hung Dock/Jake Lee is “Dea Hong Ock” whose Chinese birth date was “ST 3-9-6”. This child was born in the third year of the reign of Sun Tung in the ninth month on the sixth day.

The immigration inspector would have used the The Chinese-American Calendar for the 102 Chinese Years 1849–1951 to convert the date from the Chinese to the Gregorian calendar. The Chinese date ST 3-9-6 is October 27, 1911. Lee was actually four years older than his known birth date. The day of birth is slightly off so there may have been some confusion when Lee learned his date of birth.

Chin Shee’s initial testimony was two-and-a-half pages. On the first page she gave her children’s names, ages and some birth dates. Her youngest son, “Hung Dock”, was born “ST 3-9-6”.

Here are three documents with photographs of Dea Hung Dock. On November 25, 1913, Dea Sing prepared to bring his wife and son to America.

Form 2512, dated June 22, 1914, had photograph number 1441 of Chin Shee and Dea Hung Dock. They were on Angel Island.

Below is Dea Hung Dock’s Application and Receipt for Certificate of Identity. On July 14, 1914, number 16298 was issued to him.

Based on the 1920 census, passenger information, and Chinese Exclusion Act case file testimonies, Lee was known by three childhood names, Dea Hong Ock (1912), Dea Hung Dock (1914), Dea Hong D. (1920). When did Lee change his name?

A clue was found in the San Francisco Chronicle, August 25, 1943, which published this item about Lee and his friends.

Success Story: A dozen years or so ago, against rather pastoral backdrop of the Watsonville scene, three youngsters went around together, played football and basketball together and shared A.W.O.L. afternoons from their high school classes. Two were Chinese and one was an inquisitive Irish lad named Gallagher.

In their more serious moments they used to hang around the office of the local daily paper, the Watsonville Register. Gallagher wrote sports, and one of the Chinese boys, Charlie Leong, spent his time there trying to find out what makes a newspaper tick. The third lad, jake Lee, painted signs and sketched everything he could find to sketch.

College separated them and they went their ways, but now today they have something else in common besides their school dals [sic]: they have all arrived. Gallagher—J. Wes Gallagher—is one of the A.P.’s crack European was correspondents. Leong, who puts out the English-language Chinese Press here, is one of the best-known Chinese editors on the Coast. An last week the other member of the trio achieved the recognition of the nationally established art dealers, Raymond & Raymond. The firm’s San Francisco branch on Sutter street is sponsoring a one-man water-color exhibition—of the works of Jake Lee.

Ancestry.com has several yearbooks of The Manzanita of Watsonville Union High School (WUHS). I searched for Jake Lee and got no results. Then I searched for Charles Leong and the earliest yearbook with his name was The Manzanita, June 1927. Below is page thirty which has the freshmen class. Preceding Leong’s name is William Lee who was the only student with the Lee surname. Later yearbooks with photographs of William Lee will show he was Jake Lee.

The Manzanita 1928 had a freshman class photograph.

WUHS had two football teams, Varsity and Lightweight. Lee was on the Lightweight team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is standing, third from the left.

I believe Lee was on one of three basketball teams. In the bottom photograph is the Midget team. In the third row, Lee sits next to the coach who is on the far right.

Lee was on the Lightweight Track Team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is in the third row, fifth from the left. I believe Charles Leong is in the second row, fourth from the left.

Lee was mentioned on the following page. Individual scores for the lightweights said Lee had a quarter point.

The Manzanita 1929 had a sophomore class photograph. I believe Lee was in the front row, third from the left. Charles Leong may be standing behind Lee.

Lee was the photography editor on the yearbook staff.

Lee continued his sports participation. He was pictured on the football team in the bottom photograph, second row, sixth from the left.

Lee was in the Golden “W” Society. In the photograph Lee is in the front row on the far right.

In the top photograph is the basketball midget team with Lee is standing on the far left.

On the bottom track team photograph, Lee is in the front row. second from the right.

The Manzanita 1930 staff included Lee who handled photography, and Leong who contributed art.

Lee was in two school plays, “Long Ago in Judea” as a slave and “The Taming of the Shrew” as Grumio. In the photograph, Lee is kneeling on the second step from the floor on the left side of the throne.

Lee’s third year in athletics included the football lightweight team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is in the front row on the far right.

In the midget basketball team photograph, Lee is standing on the far right.

The bottom track team photograph shows Lee sitting in the front row on the far left.

On this page. Lee was noted as an outstanding performer.

The 1930 census was enumerated on April 11. I did not find the Dea family in this census. So I searched for William Lee in Watsonville and found the Lee family in Watsonville Junction which was an unincorporated place in Pajaro Township, Monterey County, California.

The Lee and Dea family members closely match each other in age. Dea Sing was 47 in 1920 and would be 57 in 1930. Chong Lee was 57 in 1930. Chin Dea was 48 in 1920 and would be 58 in 1930. Chin Shee Lee was 58 in 1930. Hong D. Dea was 5 in 1920 and would be 15 in 1930. William Lee was 18 in 1930. Mee Dea was 4 in 1920 and would be 14 in 1930. May Lee was 14 in 1930. Hung Lon Dea was 2 in 1920 and would be 12 in 1930. George Lee was 13 in 1930.

How did the Dea family become the Lee family? My theory is Dea Sing was a paper son whose family name was Lee. (The name Lee also appeared in his business names.) In the 1920 census, the five Lee men may have been relatives or clansmen. After the 1920 census, Dea Sing used his real name and his children had the Lee surname when they enrolled in school. The children were given English first names. Maybe Jake never spoke about his family because he wanted to protect his parents’ past.

The 1930 census said Chong Lee was a store keeper whose business was cigars. William Lee was a sign painter for a creamery. The San Francisco Chronicle said Lee painted signs.

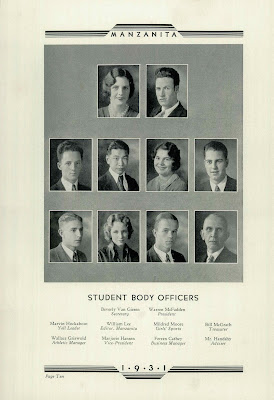

The 1931 Manzanita was edited by Lee who was also a student body officer.

Lee’s senior photograph and favorite song.

Lee, on the far left, was on the Executive Committee.

The Biology Club included Lee, club president, in the bottom photograph in the last row, second from the right.

Golden “W” list of students.

Once again Lee served as the editor of the Manzanita yearbook. Leong was in charge of senior activities.

Illustrations by Lee

Lee’s review of the track season.

Lee mentioned in stanza number nine.

Scenario by Lee

On March 16, 1934, Dea Sing (Chong Lee) and his daughter “Dea May Gunn” (aka Dea May Gue) were interviewed on Angel Island. On the first page, Dea Sing said he was born in San Francisco at 824 Grant Avenue but in his 1899 testimony the address was 622 Dupont Street. After the Great Earthquake, Dupont Street became Grant Avenue. Dea Sing said he was a merchant at Gong Lee Yuen Company in Watsonville, California.

On page two, Dea Sing stated the names, ages, birthplaces and locations of his children. Dea Sing said his son, “Dea Hong Ock”, was “24 years, born at Hom Ben Yuen Village, now attending a college near San Jose, Calif.” Page thirteen of the catalog said, “After completing his studies at San Jose State College, Lee worked as a paste-up artist for the San Francisco Chronicle.”

Dea Sing went on to say that Dea May Gunn lived in San Antonio, Texas. The catalog referred to “the return address of a sister living in San Antonio, Texas”.

On the third page, Dea Sing acknowledged that he was the sole owner of the Ong Lee Company in Monterey.

Ancestry.com has the San Jose State College yearbook, La Torre, from 1930 to 1939 except 1935. William Lee was in the 1934 yearbook. It’s not known how or when Lee got the name Jake.

Lee was mentioned in the school newspaper the Spartan Daily on page two, column one of the December 27, 1937 issue.

Charles Leong was in the 1936, 1937 and 1938 La Torre yearbooks. Years later Leong and Lee collaborated on the article, “Celestial Temples in the Golden Hills”, for the July 1950 issue of Ford Times. The publication brought them together again for “Chinatown, My Chinatown” in the February 1955 issue. The Spartan Daily, February 9, 1955, wrote about them in “Ford Times Prints SJS Grads’ Work” on page eight, column one.

Witteveen Studio, in Eugene, Oregon, published a profile of Lee. (Elaine Witteveen passed away last year and her obituary was published in the Jackson Review.) The undated profile was found on eBay several years ago and is transcribed below

The Manzanita 1928 had a freshman class photograph.

WUHS had two football teams, Varsity and Lightweight. Lee was on the Lightweight team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is standing, third from the left.

I believe Lee was on one of three basketball teams. In the bottom photograph is the Midget team. In the third row, Lee sits next to the coach who is on the far right.

Lee was on the Lightweight Track Team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is in the third row, fifth from the left. I believe Charles Leong is in the second row, fourth from the left.

Lee was mentioned on the following page. Individual scores for the lightweights said Lee had a quarter point.

The Manzanita 1929 had a sophomore class photograph. I believe Lee was in the front row, third from the left. Charles Leong may be standing behind Lee.

Lee was the photography editor on the yearbook staff.

Lee continued his sports participation. He was pictured on the football team in the bottom photograph, second row, sixth from the left.

Lee was in the Golden “W” Society. In the photograph Lee is in the front row on the far right.

In the top photograph is the basketball midget team with Lee is standing on the far left.

On the bottom track team photograph, Lee is in the front row. second from the right.

The Manzanita 1930 staff included Lee who handled photography, and Leong who contributed art.

Lee was in two school plays, “Long Ago in Judea” as a slave and “The Taming of the Shrew” as Grumio. In the photograph, Lee is kneeling on the second step from the floor on the left side of the throne.

Lee’s third year in athletics included the football lightweight team. In the bottom photograph, Lee is in the front row on the far right.

In the midget basketball team photograph, Lee is standing on the far right.

The bottom track team photograph shows Lee sitting in the front row on the far left.

On this page. Lee was noted as an outstanding performer.

The 1930 census was enumerated on April 11. I did not find the Dea family in this census. So I searched for William Lee in Watsonville and found the Lee family in Watsonville Junction which was an unincorporated place in Pajaro Township, Monterey County, California.

The Lee and Dea family members closely match each other in age. Dea Sing was 47 in 1920 and would be 57 in 1930. Chong Lee was 57 in 1930. Chin Dea was 48 in 1920 and would be 58 in 1930. Chin Shee Lee was 58 in 1930. Hong D. Dea was 5 in 1920 and would be 15 in 1930. William Lee was 18 in 1930. Mee Dea was 4 in 1920 and would be 14 in 1930. May Lee was 14 in 1930. Hung Lon Dea was 2 in 1920 and would be 12 in 1930. George Lee was 13 in 1930.

How did the Dea family become the Lee family? My theory is Dea Sing was a paper son whose family name was Lee. (The name Lee also appeared in his business names.) In the 1920 census, the five Lee men may have been relatives or clansmen. After the 1920 census, Dea Sing used his real name and his children had the Lee surname when they enrolled in school. The children were given English first names. Maybe Jake never spoke about his family because he wanted to protect his parents’ past.

The 1930 census said Chong Lee was a store keeper whose business was cigars. William Lee was a sign painter for a creamery. The San Francisco Chronicle said Lee painted signs.

The 1931 Manzanita was edited by Lee who was also a student body officer.

Lee’s senior photograph and favorite song.

Lee, on the far left, was on the Executive Committee.

The Biology Club included Lee, club president, in the bottom photograph in the last row, second from the right.

Golden “W” list of students.

Once again Lee served as the editor of the Manzanita yearbook. Leong was in charge of senior activities.

Illustrations by Lee

Lee’s review of the track season.

Lee mentioned in stanza number nine.

Scenario by Lee

On March 16, 1934, Dea Sing (Chong Lee) and his daughter “Dea May Gunn” (aka Dea May Gue) were interviewed on Angel Island. On the first page, Dea Sing said he was born in San Francisco at 824 Grant Avenue but in his 1899 testimony the address was 622 Dupont Street. After the Great Earthquake, Dupont Street became Grant Avenue. Dea Sing said he was a merchant at Gong Lee Yuen Company in Watsonville, California.

On page two, Dea Sing stated the names, ages, birthplaces and locations of his children. Dea Sing said his son, “Dea Hong Ock”, was “24 years, born at Hom Ben Yuen Village, now attending a college near San Jose, Calif.” Page thirteen of the catalog said, “After completing his studies at San Jose State College, Lee worked as a paste-up artist for the San Francisco Chronicle.”

Dea Sing went on to say that Dea May Gunn lived in San Antonio, Texas. The catalog referred to “the return address of a sister living in San Antonio, Texas”.

On the third page, Dea Sing acknowledged that he was the sole owner of the Ong Lee Company in Monterey.

Ancestry.com has the San Jose State College yearbook, La Torre, from 1930 to 1939 except 1935. William Lee was in the 1934 yearbook. It’s not known how or when Lee got the name Jake.

Lee was mentioned in the school newspaper the Spartan Daily on page two, column one of the December 27, 1937 issue.

A day or two ago I was talking to my friend Jake Lee, who is taking a course in commercial art.The Spartan Daily, January 10, 1938, published an article, “A New Flag to Wave”, about its name-plate. On page two the editor said Lee designed a new name-plate.

“You must meet Mickey Slingluff sometime,” I said. “He is majoring in the same thing.”

“I had a course with him last quarter,” Lee replied. “There were only the two of us in the class.’

“Oh, then you know him already.”

“No,” he said, “Slingluff was always absent.”

Wilbur Korsmeier, present Daily head has had Jake Lee, (incidentally a bonified [sic] art major) at work making a new streamlined nameplate. It will boast the very latest style of design, a “Gothic Script” by name. It’s definitely scheduled to make its first appearance in tomorrow’s Daily. Watch for it.The new Spartan Daily name-plate appeared the next day.

Charles Leong was in the 1936, 1937 and 1938 La Torre yearbooks. Years later Leong and Lee collaborated on the article, “Celestial Temples in the Golden Hills”, for the July 1950 issue of Ford Times. The publication brought them together again for “Chinatown, My Chinatown” in the February 1955 issue. The Spartan Daily, February 9, 1955, wrote about them in “Ford Times Prints SJS Grads’ Work” on page eight, column one.

Two SJS alumni, whose footprints have drifted together from time to time since their college days, have collaborated once more in the February issue of Ford Times. With words by Charles Leong and paintings by Jake Lee, they describe the life and times of old Chinatown in San Francisco.

Charles Leong is well-known for editing and publishing various American-Chinese editions. Jake Lee was graduated as a commercial artist, but has earned his fame as a top depicter of Western scenes in watercolor.

Lee has just completed a successful show Jan. 27 to Feb. 3 at the San Francisco Chinese YMCA. Many of the pictures were loaned by the Ford Motor Co., which owns quite a large collection of Lee’s works.Lee signed his work as Jake Lee, but sometimes he was credited or referred to as Jake W. Lee.

Witteveen Studio, in Eugene, Oregon, published a profile of Lee. (Elaine Witteveen passed away last year and her obituary was published in the Jackson Review.) The undated profile was found on eBay several years ago and is transcribed below

The Artist

Jake Lee was born and raised in Monterey, California. As a young lad he spent much of his time watching artists painting. Sometimes he would make pencil sketches along with them. He brought these drawings home to his mother, and she bought him a set of crayons. He said he was the only one in his class that had a set of 45 different colors.

When he got to high school, he was thrilled to enroll in an art class and to be introduced to watercolors. They were better than crayons because they sparkled and were much faster. He learned to work very rapidly in order to capture the movement of the surf around Pacific Grove and Carmel. His father frequently took him on trips to San Francisco. The city fascinated him—the noise, the pace, the color—everything desirable for watercolor painting. He was too shy to sketch in the stores, so he drew looking out of windows.

When it was time to go to college, he has an important decision to make. Art, after all, was a love with him, but was it a career? His father didn’t think so, and urged Jake to study architecture. He started out that way, but more and more art classes filled his curriculum. He graduated from San Jose State with as A.B., and later moved to San Francisco. Here he worked for a newspaper, but every chance he had he painted. One day, when he was painting on Telegraph Hill, he chose a quaint building as a subject. It was Shadow Restaurant, and when he was partially finished, a man came over and stood by watching. He asked what Jake was going to do with it when he finished. Jake had stacks of paintings at home and never given a thought as to what to do with them. He asked him if he would sell it. Jake was so surprised, he didn’t know what to say, and the man offered him $35. He owned the restaurant. Twenty years later, when Jake went to visit the restaurant, he met the owner again. He told him the restaurant had a fire, but one of the first things he saved was the painting. He still has it in his dining room.

Jake had his first one-man show in 1943, and has had many since. After the service, he moved to L.A., and there he played in the movies, because there were many shows using orientals. He became interested in set designing and did many stage sets for little theater groups. He also has designed murals, covers for books and Westways Magazine, illustrated stories, and has contributed over thirty paintings to Ford Times.

Lee has not yet been found in the 1940 census.

Lee was counted on line 17 in the 1950 census. He was a Los Angeles, California resident at 675 South Coronado. Lee was a freelance watercolor artist who serviced advertising agencies.

Lee illustrated the book My House Is the Nicest Place (1963) by Florence White. The author and artist were profiled on the last page.

Jake W. Lee was born in Monterey, the picturesque old town so celebrated in California history. He grew up there, attended the Monterey public schools, and went on to San Jose State College from which he graduated with a bachelor’s degree.It was while in college that he became interested in mural painting and stage design. Since then, among other things, Mr. Lee has done book and magazine illustration, his work often appearing on the covers of Westways magazine. At present he is a free-lance artist with headquarters in Los Angeles and makes his home in North Hollywood.

Lee passed away September 13, 1991, in Los Angeles, California.

Further Reading

Related Posts

(Updated December 4, 2022. Next post on Friday: Tyrus Wong in The Architect and Engineer)