Professor Leong Kai Cheu’s visit to Chinatown was reported in the following newspapers.

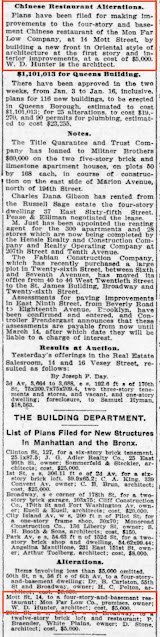

New York Evening Post, May 13, 1903

Crowds in Doyers Street

Prof. Leong, Chinese Reformer, Speaking in Theatre.

Patriotic Fugitive Welcomed by Mott, Pell, and Doyers Street Merchants—Not Much Surface Enthusiasm, But All Chinatown Out to Greet the Visitor—The Dowager Empress After Prof. Leong’s Head.

Prof. Leong Kai Cheu, who at the early age of twelve achieved the degree of B.A., and four years later was made M.A., and who is the founder and Vice-President of the “Chinese Empire Reform Association,” delivered a lecture at two o’clock this afternoon in the Chinese theatre in Doyer Street on the reform movement in China. Professor Leong has been condemned to death as often as any man in China who has lived to tell the tale. Once upon a time he was teacher in the palace of the Emperor of China, a position which he filled to the great dislike of the Dowager Empress, who is in high opposition to anything savoring of reform in China. Had the Empress Dowager had her way, Professor Leong would probably have had to lecture this afternoon with his head in his hand. However, the noted Chinaman succeeded in keeping a firm grip on his head piece and with it fled from the Chinese empire, still faithful to the reform movement.

Chinatown was not to-day in such an excess of joy over the presence of the noted reformer as might have been expected in such an enthusiastic region, and when some of the merchants were asked why it was that only one or two banners hung from the second-story windows of Mott and Pell and Doyer Streets and the fire crackers seemed to be absent, answer was made that Professor Leong, like a true reformer, was unwilling that any great amount of expenditure should be made to welcome him to the Chinese settlement in New York.

“He is a very modest man,” was the explanation of Soy Kee, a Pell Street merchant, “and he would very much rather have his countrymen present in the theatre than remain at home and raise flags and fire firecrackers.”

Although no widespread demonstration was made throughout Chinatown when Professor Leong arrived within the Celestial boundaries, the entire region was alert and waiting for him long before the noon hour. In his train, when he arrived at the Chinese theatre, were Soy Kee, Chu Si Kong, of Chicago; Charlie Yip Yen of Vancouver, B.C.; Pow Chee, the reformer’s interpreter, and Wong Wai Chee. These Celestials are to meet to-night at a banquet at No. 14 Mott Street, which is Mon Far Low’s restaurant “For All Nations,” which Mr. Kee confidentially assures all inquirers, is to last at least four hours, and to be enlivened by long speeches upon the reform movement in China.

The resident of Chinatown apparently had on their best bibs and tuckers early this morning and were standing around the entrances to their shops, restaurants, and warehouses, discussing the coming of Professor Leong. Many Chinese babies were in evidence on the doorsteps as if there were some chance, perhaps, that Professor Leong would follow in the path of Western reformers and kiss some of the offspring. The Chinese have made much of Professor Leong since his arrival in this country, and he has visited many of the leading merchants of Chinatown, in token of which these merchants made a proud exhibit of the reformer’s crimson card covered with black sprawling hieroglyphs. There are at least four thousand members in the reform associations in this city, and it is to arouse enthusiasm among them that Professor Leong has made a visit to this country. The headquarters of the association in this city are at No. 20 Mott Street, where Professor Leong was entertained yesterday at a luncheon and reception.

Leong a Fugitive.

Professor Leong has been learned ever since he was small. He was born in the Province of Kwang-Tung and at the age of nineteen, after taking the Imperial examinations, in which slim-beared men usually take part, he was chosen tutor at the Hun-On Palace, a post of distinction beside the royal family. This work did not prove entirely congenial to him and in half a year he resigned, and became editor of a daily paper, which the alert Dowager Empress quickly suppressed, its editorials proving highly distasteful to her imperial ideas. The reformer then fled to Pekin and started the Progress, which made his name famous all over the north of China, and again incurred the displeasure of the Empress. This august lady was chary about suppressing so prominent a paper, and as an apparent means of extrication from the dilemma in which she found herself, a number of viceroys and cabinet ministers suggested him for appointment to Government service. This was more than the Empress could stand, and she put her imperial foot down upon the project. Minister Wu Ting Fang wrote from Washington asking for his services as Chief Secretary of legation, but Professor Leong had other things in mind, and politely declined the office. Later, however, he accepted the directorship of Woo Nan University in a province know[n] to be one of the most conservative in all China. This did not deter Professor Leong, who continued his work of reform with signal success. After this, his work in China involved the greatest amount of risk, inasmuch as the Empress seemed determined to rid herself of his influence in the Empire, especially as numerous modern educational methods had been introduced by Professor Leong. The climax was reached when the Empress and her Manchurian vassals conspired imprisonment of the Emperor and the banishment or decapitation of his retainers and advisers. Then it was that Professor Leong fled post haste to Japan, taking refuge on a Japanese warship.

Crowds to Hear Him.

It was to hear the record of his achievements in reform in China and of his hopes for an augmentation of the strength of this movement in America that the Chinamen gathered in the theatre in Doyer Street this afternoon. Long before two o’clock a chattering crowd of Chinamen had gathered at the theatre entrance, and were elbowing and pushing their way to gain admission. Meetings in Chinese theatre are proverbially noisy, and it seemed that when the time should come for Professor Leong to make his appearance there would be a great deal of difficulty in hearing him. Professor Leong is a young man, having just reached thirty, an age which seems to leave no impress upon the stoical Celestial features, and dresses in European clothing. He does not speak English, having his fidus Achates Mr. Pow Chee always at his elbow when it is necessary to converse with those of the Western world. This is Professor Leong’s first visit to America, and he arrived here on Monday, having come from Japan by way of China.

New York Evening Telegram, May 13 1903

Chinese Reformer Here Lecturing

Professor Leong Kai Cheu Is a Fugitive, Having Incurred Displeasure of Empress Dowager.

The inhabitants, of Chinatown gathered in great force this afternoon at the theatre in Doyer street to listen to a lecture by Professor Leong Kai Cheu, founder and vice president of the Chinese Empire Reform Association.

The professor arrived Monday from Japan, where he had been for the benefit of his health—not that he was ill, but because he feared he might contract that complaint, so common and fatal to reformers in China, decapitation.

The Chinese have made much of Professor Leong since his arrival in this country, and he has visited, many of the leading merchants of Chinatown. There are at least four thousand numbers in the reform associations in this city, and it is to arouse enthusiasm among them that Professor Leong has made a visit to this country. The headquarters of the association in this city are at No. 20 Mott street, where Professor Leong was entertained yesterday at a luncheon and reception.

Professor Leong has been learned ever since he was small. He was born in the province of Kwang-Tung and at the age of nineteen he was chosen tutor at the Hun-On Palace, a post of distinction beside the royal family. This work did not prove entirely congenial to him and in half a year he resigned and became the editor of a daily paper, which the alert Dowager Empress quickly suppressed, its editorials proving highly distasteful to her imperial ideas. The reformer then fled to Pekin and started the Progress, which made his name famous all over the north of China, and again incurred the displeasure of the Empress.

Later be accepted the directorship of Woo Nan University in a province known to be one of the most conservative in all China. This did not deter Professor Leong, who continued his work of reform with signal success. After this, his work in China involved the greatest amount of risk. Inasmuch as the Empress seemed determined to rid herself of his influence in the Empire, especially as numerous modern educational methods had been introduced by Professor Leong. The climax was, reached when the Empress and her Manchurian vassals conspired imprisonment of the Emperor and the banishment or decapitation of his retainers and advisers.

Then it was that Professor Leong fled post haste to Japan, taking refuge on a Japanese war ship. In his train when he arrived at the Chinese theatre were Soy Kee, Chu Si Kong, of Chicago; Charlie Yip Yen, of Vancouver, B. C.; Pow Chee, the reformer’s interpreter and Wong Wai Chee. These Celestials are to meet to-night at a banquet at No. 14 Mott street, which is Mon Far Low’s restaurant “For All Nations.”

China’s Boss Reformer Here

Leong Kai Cheu Is Seeking to Arouse Enthusiasm.

Had Trouble Running a Newspaper in His Native Land, So He Tried Awhile in Japan—Will Lecture Here Almost Daily—Dinner in His Honor Last Night.

Prof. Leong Kai Ka Cheu, reformer, late of China, but now resident of Japan, where he edits a new reform newspaper every day, gathered all New York’s Chinatown around him in the Chinese theatre in Doyers street yesterday to listen to a lecture on reform. Prof. Leong’s friends say he is the William Travers Jerome of China—“man who acts by day and night.”

Prof. Leong is a hustler. He got his degree of A. B. when he was only 12 years old and the degree of A. M. when he was 16. When he was 19 he took the Imperial examinations and became tutor at the Hun-on Palace, according to his friends. He tutored for a year and a half ht and then started a daily newspaper.

The editorials of Prof. Leong were so radically that the Empress Dowager made him shut up shop. He went to Pekin and tried to run his paper again. The Empress for some reason apparently didn’t want him killed or didn’t know just how to accomplish it, so she finally got him the job of director of the Woo Nan University, hoping that he would keep quiet.

He didn’t remain quiet and when the Empress Dowager’s enemies heard, just before the outbreak of the war in China, that she was going to decapitate a lot of people he skipped to Japan. A Japanese warship helped him in his escape.

Arrived in Japan, Prof. Leong saw no reason why he should not continue editing a reform newspaper for benighted Chinese. When the Chinese officials saw the reform editorials they said the paper must not enter China. Prof. Leong thereupon changed its name and got out another issue before the officials discovered the subterfuge.

“And this he did at every ever issue,” said Loo Sin of 14 Mott street, a member of the committee of welcome. “It was like this: One day the paper would be the “Sun.” Next day it would be the “World” and next day the “Herald” and so on, and so on. Names are easy to get.”

Prof. Leong arrived on the Pacific Coast several weeks ago and is making a tour of the country to interest Chinese in reform at home. By reform he means more schools, hospitals, a Chinese navy for the Chinese and no more graft for the Manchurians. The war cry is “China for the Chinese.”

Prof. Leong, who is only 30 years year old and who wears American clothes, is accompanied here by his interpreter, Pow Chee; Chu Si Kong, head of the Chinese reformers in Chicago; Charlie Yip Yen, the boss reformer of Vancouver, B. C., and two others.

They arrived at the Grand Central Station on Monday night and were met by a reception committee of twenty-six New York Chinamen, each of whom wore a silk hat and a big yellow badge. Prof. Leong and his travelling companions lectured yesterday afternoon to about about 2,000 Chinese in the little Doyers street theatre. As many more were unable to get in.

Leong and his associates will be here for several weeks. Lectures will be held almost every day. Last night the whole party met the representative men of Chinatown at Mon Far Low’s restaurant at 14 Mott street. The only toast was “Reform.” Proprietor Mon Far Low, who is no relative of Mayor Low, provided champagne in which to drink the toast.

%20p5.jpg)

The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (New York), August 30, 1903, noted the dining experience by one of its residents.

Lives to Tell Tale.

Rochester Man Passes Through a Weird Experience in China Restaurant.

Thomas Verhoeven, of this city, has just returned from a trip to New York. Mr. Verhoeven has many surprising incidents to relate connected with his trip, but the one he delights in dwelling on the longest is a dinner that he took at the Mon Far Low, the leading Chinese restaurant in New York city, conducted by Loo Lin.

The most surprising thing connected with the repast is that Mr. Verhoeven is alive to tell the tale, for after a man has dined on “Hing Sun Chop Sooy,” “Chu Gay Squab,” “Sweet and Pungent Chicken,” “Edible Birds’ Nests,” “Yellow Fish Brain,” “Sharks’ Fins,” “Bok Du Qual Chu,” “Ya Ko Main,” and many other like delicacies, if he escapes the grave, death can have few terrors.

The New York Times, March 29, 1904

Chinatown to Have Birthday Party.

Francis M. Hamilton, Solicitor to Collector Stranahan, and several other members of the Customs Service received elaborately engraved invitations yesterday from Mr. and Mrs. Lee Yick Yon [sic] for a banquet at 14 Mott Street next Thursday evening in honor of the birth of their son. Lee Gin Yon. Lee Yick Yon is a large importer of Chinese merchandise.

New York Herald, April 1, 1904

Occident and Orient at Chinese Feast

New Yorkers in Evening Dress Guests of Mr. Lee Yick You at Typical Birthday Festival.

Seventy women and men clad in conventional evening dress and a score of the Sons of the Celestial Empire sat together last evening at a dinner unique in its appointments and lavishly strange and generous as to its edibles.

The host of the entertainment, which was served in a private dining room of Mon Far Low’s Chinese restaurant, at No. 14 Mott street, was Mr. Lee Yick You, a wealthy importer, of No. 34 Pell street, and in giving the feast the host was following out an ancient custom of the Yellow Empire and honoring Mrs. Lee Yick You, whose youngest child, Master Lee Gin You, was one month old yesterday.

The guest was Mr. Francis M. Hamilton, Solicitor of the Custom House. Mr. Yan Phou Lee, a graduate of Yale and a wealthy importer of this city, presided.

The decorations were exceedingly ornate, the tables being covered with flowers strange in form and color, while on the walls and suspended from the ceiling were silken banners bearing the device of the dragon.

During the dinner Master Lee Gin You, clad in rich robes of red silk and as fat and wide awake a little youngster as ever opened his eyes on an evening gathering, was brought in by a Chinese maid and passed around among the company. The ladles were permitted to kiss the youngster, and his health and that of his mother was drunk by all present. Master You looked at the proceedings through his almond shaped eyes, but made no comment.

The New York Press, April 1, 1904

Chinese Baby at a Dinner.

Many Government Employee Guests of Proud Father, Lee Yick You

Seventy men and women clad in conventional evening dress and a score of Chinese say together last evening at a dinner odd in its appointments.It was served in a private dining room of Mon Far Low’s restaurant in No. 14 Mott street, and the host was Lee Yick You, a wealthy importer of No. 34 Pell street. He was honoring Mrs. Lee Yick You, whose youngest child, Lee Gin You, was one month old yesterday. The chief guest was Francis M. Hamilton, solicitor of the Custom House, and the other guests included a dozen members of the United States Appraisers’ staff. Yan Phou Lee, a graduate of Yale, presided.

The tables were covered with strange flowers, and there were silken banners and lanterns on all sides. The menu included such dishes as pineapple chicken, fried spring squab, bird’s nest soup, sharks’ fins, yellowfish brains, jun gee duck and but bow chicken, all go which were washed down with real Sui Shen and long sou teas.

Lee Gin You, in rich robes of red silk, was brought in by a Chinese maid and passed around among the company. The women were permitted to kiss the youngster, and his health was drunk.

The New York Times, April 1, 1904

Big Fete for Celestial Baby.

Company Honors Master lee Gin You at Banquet in Chinatown.

Seventy women and men clad in conventional evening dress and a score of the sons of the Celestial Empire were the guests at dinner last evening of Lee Yick You, an importer at 34 Pell Street. It was served in a private dining room of Mon Far Low’s Chinese restaurant at 14 Mott Street. In giving the feast the host was following out an ancient Chinese custom in honoring Mrs. Lee Yick You, whose youngest child, Master Lee Gin You, was one month old yesterday.

The guest of honor was Francis M. Hamilton, Solicitor of the Custom House. Yan Phou Lee, a graduate of Yale, and a wealthy importer of this city, presided. The tables were covered with flowers, strange both in form and color, while on the walls and suspended from the celling were silken banners bearing the device of the dragon, and bewildering as to color were other flags, banners, and lanterns.

The menu included dishes dear to the Celestial heart, such as pine apple chicken, fried Spring squab, mushroom chicken, bird’s nest soup, shark’s fins, yellow fish brains, chestnut chicken, and Jun Gee duck, washed down with Sui Shen and Long Sou teas specially imported for the occasion.

During the dinner Master Lee Gin You, clad in rich robes of red silk, was brought in by a Chinese maid and passed around among the company. The ladles were permitted to kiss the youngster, and his health and that of his mother was drunk by all present.

Complimentary addresses were made by Mr. Hamilton, Miss Harriet Quimbey, a newspaper woman of San Francisco; Capt. William Lee, Treasury Agent D. E. Galboldy, and Capt. Howard Patterson of the New York Nautical School.

14 Mott Street on the right;

Mine Far Low Restaurant sign

Date unknown

The New York Times, November 2, 1904, said

Chinatown’s Cupid Busy.

Winged Three Couples in One Night at Chop Suey Parlor.

Three men, two maids, and a dashing young widow made a hastily planned trip through Chinatown one night six weeks ago. Before the outing ended the Chinese Cupid had paired them off. Two of the three couples are already wedded. The third will follow suit the first week of the new year.

From all accounts the little god began to get busy when the chop suey was served in Loo Ling’s restaurant, 14 Mott Street. The first wedding took place within a month, when ex-Congressman Henry Cassorte Smith of Michigan, now general counsel of the Michigan Central Railroad, and Miss Virginia Bassett were married at the Church of the Transfiguration. ...

Mon Far Low’s fine was rescinded according to

The City Record (New York), November 4, 1904.

Resolved, That the Corporation Counsel be and is hereby requested to discontinue without costs the actions against the following named persons for violations of the Sanitary Code and of the Health Laws, the Inspector having reported the orders therein complied with, or the nuisances complained of abated, a permit having been granted or violations removed, or the orders rescinded, to wit:

Mon Far Low 1,022

14 Mott Street, second building from

the right; circa 1904

* * * * * * * *

SIDEBAR: Loo Lin’s Wife’s Trip to America Was Tangled in Red Tape

New York Herald, May 25, 1903

Chinese Wife Asks Aid of President

Barred from Husband by Red Tape, Mrs. Loo-Lin Appeals to Mr. Roosevelt.

Effect of Queer Law

Because He Owns Restaurant She Is Classed as Laborer’s Wife.

Both Are Well Educated

Woman Detained at San Francisco by Immigration Authorities for Weeks.

Loo Lin Ben, leader of the progressive element in New York’s Chinatown, a man of culture and learning, thoroughly Americanized in most of his ways, announced last night that he had fallen back upon his early philosophy to comfort him in his distress resulting from the treatment his wife is receiving at the hands of the United States immigration officials. Mrs. Loo Lin, a woman of refinement, a teacher of recognized ability in her own country, has been held a prisoner in the detention pen in San Francisco merely because her husband, though a merchant, happens to own an interest in a restaurant.

For some reason the United States government chooses to class the owner of a restaurant as a laborer, and as a Chinese laborer has no right to bring his foreign wife to this country little Mrs. Loo Lin must suffer until some official has the nerve to cut the red tape that bars her from American shores.

Loo Lin’s countrymen regard him with affection, and they trust him. His American friends also trust and respect him. He has done more than any other person to drive crime from Mott and Pell streets. He is a member of the First Baptist Church, Seventy-ninth street and Broadway, and he has been active in forwarding the interests of the Morning Star Mission for Chinamen. For several years he was at the head of that mission, and he has long been a member of the Young Men’s Christian Association.

Loo is the senior member of the firm of G. Ton Toy & Co., at No. 3 Mott street, where a General merchandise business is carried on. He is also associated with his brother in the restaurant at No. 14 Mott street, known as Mon Far Low, which translated into English, is “The Restaurant of Countless Flowers.” To a reporter for the Herald Loo Lin yesterday told the following story of his troubles:—

“I try to be patient, but there is nothing that I have learned since my arrival in the United States, fifteen years ago, that gives me any assistance. I know that everything will come out right in the end, and in the meantime I must be a Chinese philosopher.

“In the first place, my wife is not a woman of the ordinary type known in this country. She is progressive, is well educated, has been a teacher in Canton for several years, her writings have been regarded as meritorious, and, finally, she has been the editor of a real newspaper, devoted to the interests of Chinese women.

“Well as I like America and the ways of Americans, I desired a wife of my own race. I wanted to marry a girl whom my mother would approve. So it happened that five years ago I returned to China. There I was introduced to Mak Chue by Mrs. R. H. Graves, the wife of the American medical missionary in Canton. Mrs. Graves, who, with her husband, is now making a visit to her relatives in Maryland, had known Mak Chue for many years, and knew her to be a bright girl and of a nature that would permit her to enjoy life in the United States.

“Mak Chue was then nineteen years old, and to me she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. Well, I wanted Mak Chue for my wife, but I would do nothing without the approval of my mother, the good Liang Loo. To her I went, and to my joy found that she approved Mak Chue and was more than willing to accept her as a daughter-in-law. We were married, and there were present when the ceremony was performed my mother and my sisters. Loo Fong and Loo See, and among others Dr. and Mrs. Graves and Mrs. Claudia J. White, who is now living in San Francisco, but who was then a teacher in Canton. My wife went to live with my mother, who was to teach her the traditions of my family. I returned to New York, it being understood that my wife would come to me at the end of five years.

“Now she has come to make my home her home, and she is held a prisoner in the detention shed on the Pacific Mail wharf in San Francisco. She has been there a month. But she is a philosopher and she has not yet lost confidence in the goodness of the Western World. We are to live not here in Chinatown, but up where there is more light and air and sunshine. My wife will teach in Chinatown, and, indeed, arrangements have already been made for her to take a class of children who do not understand the English language. But when will she be here? I do not know. She is held a prisoner because I own this restaurant and so must be called a laborer. If I sold tea and nothing more there would be no trouble. However, I have many good friends and I am confident that the red tape will soon be cut and everything will be well. I have appealed to President Roosevelt and I am told that he will help me. Perhaps it will not be necessary to wait for his return to Washington. I hope not.”

Loo Lin Talks of Wife’s Woes

Husband of the Chinese “New Woman” Hopes for the Best.

Believes Her Imprisonment in San Francisco Will End Soon.

New York, May 24.— The Herald will say to-morrow: Loo Lin Ben, leader of the progressive element in New York’s Chinatown, a man of learning and thoroughly Americanized in most of his ways, announced to-night that he had fallen back upon his early philosophy to comfort him in the distress resulting from the treatment his wife is receiving at the hands of United States immigration officials. Mrs. Loo Lin has been held a prisoner in the detention pen in San Francisco because her husband, though a merchant, happens to own an interest in a restaurant. Loo is senior member of the firm of G. Tomtoy & Co., at 3 Mott street, where a general merchandise business is carried on. He is also associated with his brother in a restaurant at 14 Mott street, known as Mon Far Low, which, translated into English, is “The Restaurant of Countless Flowers.” Loo said to-night:

My wife is not a woman of the ordinary type known in this country. She is progressive, is well educated, has been a teacher in Canton for several years, her writings have been regarded as meritorious, and, finally, she has been editor of a real newspaper devoted to the interests of Chinese women. She is held a prisoner in the detention shed on the Pacific Mail wharf in San Francisco. She has been there a month. My wife expects to teach in New York and arrangements have already been made for her to take charge of a school for children who do not understand the English language. I have many good friends and I am confident that the “red tape” will soon be cut and everything will be well. The case has been appealed to Washington and I am receiving assistance from men of high standing in New York.

The World will say to-morrow that Loo Lin has friends who concluded that as Americans they would not stand by and see what they deemed a piece of stupidity and injustice pass and they determined that Mrs. Loo Lin should come in. The appeal will reach Washington in a few days, and there is no doubt, says the World, that the department will overrule the absurd decision of the New York inspector, who reports Loo Lin to be a “laborer” because he owned a restaurant in addition to his mercantile business.

There are several peculiar things about the manner which the case of Mrs. Loo Lin has been handled that will call for action at the proper time, say the friends of Loo Lin.

Mrs. Loo Lin, the Chinese “new woman,” who has been detained in the sheds of the Pacific Mall Steamship Company, by instructions of the Chinese Bureau, for more than a month, pending the unraveling of a “red tape” tangle involving her right to land, is quite ill, and has requested the attendance of a physician. She has been enduring in great patience her enforced imprisonment, but her general health has been impaired by the long confinement. Sympathizers in this city are doing as much as possible to provide for her comfort, though handicapped by her cheerless environment.

%20p7.jpg)

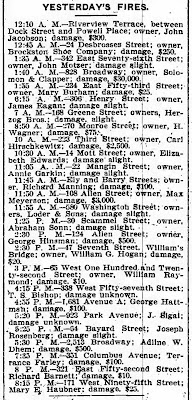

New York Herald, September 15, 1903

Chinese School Failed to Open

Kindergarten in Mott Street Missed Its teacher and Operations Were Postponed.

Mrs. Loo Lin Was Delayed

Held in San Francisco, the Head of the Institution Had to Provide a Heavy Bond.

There was one part of the local school system which did not get into operation yesterday, and that was the kindergarten to be conducted for Chinatown, at No. 11 1/2 Mott street, under the auspices of the New York Presbytery. The reason was the non-arrival from China of the pretty wife of Loo Linn, a well known merchant of that section of the city, who lives at No. 14 Mott street.

Mrs. Loo Linn came from China to San Francisco last April with the Rev. Dr. Gray, but was held there under the Chinese exclusion act for forty-two days. Her husband has been in this city for twelve years. He made some money in the laundry business and seven yearn ago went back to China and was married. He returned to the United States the following year, leaving his wife after him in Canton, where she was a teacher in the college attached to the Baptist mission there. Since he has prospered as a merchant.

He enlisted the sympathy of the mission authorities here and in San Francisco, and the necessary papers having been forwarded to Washington she was released under a bond of $1.000. furnished by the Canadian Pacific Railroad. She then went to Montreal, where she has been staying since.

She is expected to arrive in this city to-day, and will receive a warm reception in Chinatown. She will take charge of the Chinatown kindergarten at once.

Kept Apart by Red Tape.

Mrs. Loo Lin, the Christianized Chinese wife of Loo Lin a restaurant keeper at 14 Mott street, and who has been the subject of much correspondence between tho port authorities and her Christian missionary friends, reached her husband safely last night, exactly five months after leaving the Canton Baptist Academy.

All her troubles in getting into the country were because she did not carry with her from China the proper passports. She came with the credentials of a merchant’s wife, and upon her arrival at San Francisco learned that restaurant keepers were not officially recognized as ”merchants.”

The Rev. R. H. Graves and his wife, who accompanied her, offered the Government authorities all sorts of identifications and recommendations, but it was impossible to sever the red tape until a new set of passports arrived from China.

Mrs. Loo Lin was detained in San Francisco, but the Canadian Pacific Railroad put up a $1,000 bond, under which she was allowed to go on to Montreal to live with missionary friends. Last month passports identifying her as a Christian missionary teacher arrived but it was not until Monday that she went before United States Inspector F. W. Berkshire at Malone, N. Y., to be passed upon.

She was permitted to go as soon as it was satisfactorily established that she really intended to do mission work. Miss Helen F. Clark of the New York Foreigners’ Mission Society, who was her sponsor before the authorities, brought her to join her husband.

Loo Lin met his wife at the Grand Central Station, accompanied by a party of his Christianized Chinese friends. Husband and wife kissed in true Occidental fashion. Mrs. Loo Lm was dressed in blue clothes of a sober cut, not unlike the Salvation Army uniform. She took a great interest in her husband’s restaurant, and spent her first hour at home in inspecting his kitchen.

New York Tribune, September 23, 1903

Loo Linn Gets His Wife

Chinese Woman Arrives in Mott-st. and Is Happy.

After a separation of five years, Loo Linn, the proprietor of the Man [sic] Far Low restaurant, at No. 14 Mott-st., and his faithful young wife were reunted [sic] last evening at the Grand Central Station. The story is a romance of the Chinese immigration laws. …

Spoke in Greendale.

First Chinese Woman That Many Have Seen Around Here.

The people of Greenport had an unusual treat last Sunday evening. Mr and Mrs Loo Lin, formerly of Canton and now of New York, spoke and sang in the Greendale Reformed church both in English and Chinese. Mr Loo Lin has made his home in this country for several years. He is the prosperous proprietor of a high class Chinese restaurant at 14 Mott Street, New York city. Mrs Loo Lin has been for some time a Bible reader in Canton. She desired to join her husband in this country but such is the stringency of the law excluding Chinese that it is only after months of waiting in Montreal that she has at last been enabled to enter as a Christian worker. She expects to do Christian work and teaching among the Chinese women and children of New York, of whom there are more than a hundred. Mr Loo Lin has the bearing of a Christian gentleman, while his wife, the first Chinese woman that many around here have seen, has the fair face and gentle manner that proclaim the lady. They are at present the guests of Mr and Mrs Seaman Miller of Germantown and New York, and it was through their kindness that the people of Greenport enjoyed and profited by this unusual exercise.

%20p8.jpg)

Comes From China to Teach

Mrs. Loo Lin’s Mission to Her Countrywomen Here.

New China Domestic.

Loo Lin, the Father of a Nine Pounder Eligible for the Presidency.

Four Chinamen were standing in front of Loo Lin’s place at 14 Mott street early yesterday morning. Loo Lin is one of Chinatown’s most prosperous and popular merchants.

A little man in homespun turned into Mott street from Chatham Square. The yellow skin of his chubby face was puckered into folds with a smile. He looked velly happy and velly proud.

There were nudges and gestures and a wise wagging of head among the four Chinamen in front of 14. They advanced to meet the little man with a smile and to meet the little man with a smile and stopped in front of him in a businesslike way. He stopped also, widened his smile, closed his eyes in a way suggestive of a wink and said something that didn’t sound at all like a description of a newly born Chinese boy. The little man was Loo Lin.

Soon afterward the smoke of burning joss sticks floated in thick clouds from the windows of Loo Lin’s place and from the windows of the places of his friends in Mott street. Peacock feathers and other things of many colors suggestive of joy and prosperity appeared one the balconies and a crowd filed into Loo Lin’s restaurant where they jabbered congratulations, took more than a few drinks of white stuff, which looked like gin, but wasn’t, and ate rice. It’s pretty certain that no other little Chinese upon his arrival in this country, ever raised so variegated a fuss in Chinatown as little Loo. It’s pretty certain also that Loo Lin never knew that he had so many friends till yesterday.

The blow-out cost him many dollars. The youngster—none pounds—arrived at Loo Lin’s home in Brooklyn last Sunday night, but yesterday was the first time Loo Lin had appeared in Chinatown since the event. The four friends who stood in front of his place representing other Chinamen with appetites, had been on the watch over since the report of the new arrival reached Mott street.

The mother has been in this country for about two years. When she came over she was held for several months by the immigration authorities in San Francisco and Canada and Loo Lin had much more trouble in getting her free from them than he had had in winning her affection.

%20p3.jpg)

%20p6.jpg)

%20p5.jpg)

%20p19.jpg)

%20p7.jpg)

%20p8.jpg)