Residents of 14 Mott Street, lines 34 to 44, counted in the 1905 New York State Census.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, July 1, 1905 listed Mon Far Low.

The New York Times, March 15, 1908

Hard Times Chased Out of ChinatownFinancial Stress Can’t Find Lodging There and Business Is SpreadingJust Ask the ‘Plofesssor’He Is the Man Who Fashions Wonderful Things in Jade for Those Who Wear JewelsProsperity has visited the firm of Ten Wah & Co., 32 Pell Street, where they “guarantee the works and take back the goods at 90 per cent,” to such an extent that the firm is importing three more expert goldsmiths, two from China and one from San Francisco. When the newcomers arrive the firm will move into a fine, new, large store, for, as was explained, “no loom for thlee more men here.”Ten Wah & Co., which provides all the jewelry for the “first families of Chinatown,” at present occupies a small part of the second story of 32 Pell Street. The front section, 6 feet by 9, contains the work bench, counter, anvil, turning lathe, the bookkeeping accoutrements, two stoves, a crockery closet, and the teapot and pipe of the establishment.The rear alcove is the sleeping apartment of the four goldsmiths, who stay there to watch the valuables in the shop, for there is a good-sized fortune in gold the jewels tucked away in the little wooden drawers of the battered counter.When the reporter expressed surprise at the amount of valuables in the tiny place, he was told of the birthday party recently given by a merchant of Chinatown in honor of his son and heir, aged one month, The very small Celestial received presents of gold jewelry weighing altogether three American pounds, practically all of which came from this one shop.The prosperity of the Chinese jewelers is not derived from the practice of the “early to bed, early to rise” principle. When the reporter called at noon the work for the day had not even been started. By the crockery case stood Wang Wah partaking of a frugal breakfast of tea. Near the stove another workman was performing his praiseworthy if ultra-conservative ablutions. Sounds from the rear indicated that the other guardians of the treasure were just arising. A call in the afternoon found the shop deserted, save for one solitary watcher, who responded, “hulloa—good-by,” and nothing more, to the questions asked him.A storekeeper possessed of a more extensive English vocabulary came to the rescue. “The jewelry store? You want see ’em work? Not to-day. They no work to-day. Come in the evening. They do all the jewelry at night. Why? Quiet then: who knows?”Whether of not the work is done at night for the sake of greater quiet, 8 P. M. is the proper calling hour at 32 Pell Street. The little shop was full of business. In the furthest corner sat Chan Quee, the “plofessor of jade,” as his employer calls him. To be a professor of jade one must be able to tell by the appearance of a lump of serpentine whether the jade crystals which have formed within will be of first quality or not, for jade is bought “by the guess” in China.The correct guessing of the expert means wealth to the employer, but in China the “plofessor” received 25 cents daily for his skill. He is now growing rich in New York on $30 a week. Lung Kitt melts the metal at his blast pipe, while Lu Way rolls the gold wire into wonderful filagree patterns of his own designing.Wang Wah stamps the thin sheet gold in leaden moulds; there are a few hundred kinds of these. Some have written blessings or good-luck charms. Others have dragons, tiny Buddhas, fishes, crabs, and so on indefinitely, After the stamping Wang Wah beats out the pattern with some of the many fine hammers, each as exact as a dentist’s drill.None of the men spoke English, but they called in the silent partner, Loo Lin who keeps the Mon Far Low restaurant at 14 Mott Street, and also a clothing store in Pell Street. Although the silent partner of the affair, Loo Lin converses quite fluently. ‘Yes, we make all by hand. Necklace, bracelet, rings, and nutpicks.”When an American eats at a Chinese restaurant he is content to spear his preserved nuts with the humble toothpick, but the merchants of Chinatown keep wonderfully decorated prongs made of pure gold to use on state occasions. For the “Melican” patrons, and the store is well known to American connoisseurs, they make watch chains and cuff links. A set of gold-mounted jade cuff links costs $18.Jade is still the most popular stone among the Chinese, in their native country it is worn as a charm to keep off evil spirits, but the Chinamen in this country, according to Loo Lin, have ceased to believe in its efficacy as a “good-luck” piece. “I tell you a story,” pursued the silent partner, “A Chinaman in San Francisco blings his wife flom China. She have a big jade bracelet. He say: ‘Why you wear that?’ She say: ‘It is good luck. If I fall it is stlong, and I do not bleak my arm.’ You see, she superstitious. He say: ‘You go up thlee stories and jump to the glound, and when you not hurt yourself then I, too, wear a bracelet for good luck.’ You see, he was not superstitious no more. He been in America.”Loo Lin spoke of the coming change in the business with pride.“We have so many orders we cannot make them all. We have send for thlee more men, veely hard to get them. Then we move into a big store—not like this—with a show case.”When the three more goldsmiths arrive, and Ten Wah’s firm moves from its cramped quarters, Chinatown will lose one of its picturesque corners, for the new place will be run on the American plan. There will be a show room in front for customers, and the work rooms will be hidden behind.No longer will visitors be able to see the “plofessor of jade” at his bench. No longer will the faithful guardians of the treasure sleep beside their handiwork, for Ten Wah has bought a large and shining American safe to hold his creations of gold, jade, and ivory.“Big safe, yelly stlong,” finished Loo Lin with pride in the progress of his firm. “Big American safe, taller than me,”

In the photograph below, 14 Mott Street is on the right. The sign for Mon Far Low is clearly legible. Buildings 14 and 16 Mott Street were draped in mourning the death of Emperor Kwang-Su who died in November 1908.

The New York Evening Post, November 18, 1908, said

Joss Row in Mott StreetOne Temple Mourns Emperor; The Other Doesn’t

At No. 16 the Blue and White Drapery Is Out and the Dragon Flag Is at Half-Mast—But There’s No Love for the Manchus at No. 20—Prayer Ships Are the Same Size.On the front of the Joss House at No. 16 Mott Street are draperies of white and blue, the mourning colors, for the dead Emperor. The Joss House at No. 20 Mott Street is not so draped, and isn’t going to be, and so, by this fact, incidental to the close of a reign in China, is revealed a secret of the Oriental colony that shimmers and sightseers would not have learned otherwise.But it is evident now that Chinatown has its church row just like any New England hamlet, with the orthodox and the liberal meeting-houses set on opposite sides of the village green, figuratively making faces at each other.And like the village churches, each of the Joss Houses claims to be the best and oldest and only true Joss House.On the one at No. 16 Mott, there was the sign in English, “The Main Temple.” On the rival temple, the legend read: “The oldest Joss House in the United States, established 1874.” But those signs didn’t necessarily convey the idea that there was friction between the priests and the congregations. The real truth was learned when an English-speaking Chinaman was asked why there was no blue and white bunting on No. 20, and why the yellow sun and dragon flag on that building was not down to half-mast. The man appealed to was evidently a worshipper at the Main Temple, for he spoke with contempt of No. 20.Monopoly of Patriotism.“That’s no good,” said the Chinaman. “Go to Main Temple, the real Joss House at 16.”When convinced that his questioner had no offering of tea or chicken for either altar, but merely wanted to know about the difference in belief as to bunting, the Chinaman explained that the Chinatown worshippers at No. 20 were all haters of the Manchus and so would not drape their building to honor the memory of a Manchu Emperor.“No. 16, all patriots,” he added. “Emperor is Emperor, Manchu or not, so the Main Temple put on mourning and lowers the dragon. No. 20, no good. Just a show for white people in automobiles.”Beyond telling why No. 20 would not put on mourning for a Manchu, the pillar of the Joss House at No. 16 could not explain why the temples were not in accord. And there is nothing in the joss houses themselves to indicate on what rock of dogma, the split came.As many incense sticks are burning in one as in the other, and, incidentally, the price per package which sight-seeing heathen are charged at each place is the same. The prayer papers that are burned at the altars are exactly as long and as wide at No. 16 as they are at No. 20, and neither high priest can say truthfully that his burners are more beautifully embroidered or that his altar is more wonderfully carved than that of the other high priest.In the blue and white draped temple a Chinaman with a basket full of savory and steaming offerings of rice and nuts and dried duck was bumping his forehead on the floor in front of the altar at No. 20, but at the same time another Chinaman was brewing fragrant tea in front of the Joss at No. 16; and one worshipper seemed just as devout as the other. So an hour among the temples was not sufficient for a layman to get at the truth of the matter.It may be a safe inference that the advocates of No. 16 are more devoted than their rivals, because to get to the altar, they have to climb three long flights of dark back stairs, the same stairs that so many timid sight-seeing persons have ascended With nervous, squeamish fear that perhaps they should have been contented with buying Joss House picture postal cards, instead of actually visiting the place.At the other temple, the Joss is only two flights up, and the high priest thinks that it is much easier for aged Chinamen to come there and much more convenient for Americans to buy their altar souvenirs from him.

The New York Herald, November 19, 1908, printed a photograph of buildings, at 14 and 16 Mott Street, draped in Chinese mourning colors blue and white.

The New York Sun, November 19, 1908, also reported the differences between the Joss Houses at 16 and 20 Mott Street.

The Bystander, December 30, 1908, printed a photograph of 14 (right) and 16 Mott Street covered in drapery. “The streamers are purple and white.”

The Chinese Students’ Monthly, Conference Number, 1909

New York Daily Tribune, July 13, 1909

Elsie Sigel Poisoned.Nature of Substance Used to Be Determined by Further Analysis.Professor George A. Ferguson, of Columbia University, by a chemical analysis, has detected the presence of poison in the vital organs of Elsie Single. He will make further tests to-day to determine the nature of the poison.The finding of Professor Ferguson confirms the evidence submitted to the police ten days ago that a Chinaman tried in vain on the day before the murder to buy poison at a drug store near the house at No. 782 Eighth avenue in which the girl’s body was found in a trunk, and that on the night preceding Elsie’s death a prescription for a powerful irritant poison was filled at another drug store near the house.Detective Fred Brickley, of the Elizabeth street station, was approached yesterday by a woman who wanted to see Captain Galvin privately in regard to the Single case. The woman told Detective Brickley that her name was May Ella Stewart. It was learned that a woman variously known as May Ella Stewart and Elizabeth Stewart had been connected with various Chinese missions, and that she knew Leon, Elsie Sigel and Mrs. Sigel.Miss Stewart lived with the family of Lui Lin, keeper of a restaurant at No. 14 Mott street, in their home at No. 33 Oliver street until recently. She left the Oliver street house to go to Brooklyn, and is now staying with friends on Long Island.Inspector McCafferty was reported yesterday as saying that the police believed Leon was killed at the same time that Elsie Sigel met her death, and that the police search for Leon was merely perfunctory. It is not doubted that the police search for Leon has been perfunctory, but it is officially admitted that the police have a copy of a telegram sent by Leon to Yung Dat on June 13, four days after the death of Elsie Sigel.

New York Sun, December 29, 1909

Wu Ting-Fang Says Good-By... In the rooms of Mon Far Low another dinner was given to the newly appointed New York Consul. Yang Yu Ying. Many of the local merchants and business men were there, as well as a few of the attachés of foreign legations.

The Library of Congress has two photographs of Mott Street.

Left to right: building numbers 16, 14 (Flowery Kingdom Restaurant),

12 (second floor flags, Young China Association) and 10, circa 1910

Residents of 14 Mott Street counted in the 1910 United States Census.

The New York City Telephone Directory, October 1910 listed Mon Far Low.

New York Herald, October 23, 1910

The Unsuspected Wits of Some Waiters... Brawn, however, was not exactly what I was searching for. Was there no Waiter Artistic to be found among the greater deserts of the New York dining room?Yes; he was discovered presently, an ivory, tint Oriental of the name of Lee Ti, consecrated for some few months to art—while his savings held—but recently the servitor of chop suey and other confections at the Mon Far Low, which is Loo Lin’s and is in Chinatown.Lee Ti is small and quick moving, and has shining Oriental eyes, bright as lizards. He will tell you (although you must be very diplomatic to tempt his confidence) that he has been here since he was a boy. He once was wealthy, but his material estate has fallen, though he bears his cross and his noodles more cheerfully than might most of us. ...

New York Herald, January 18, 1911

Manhattan Building Plans.Mott St. 14; to a 4 story & basement restaurant; Mon Far Low Co. premises, owner; W D Hunter, architect.....5,000

The New York Press, January 18, 1911

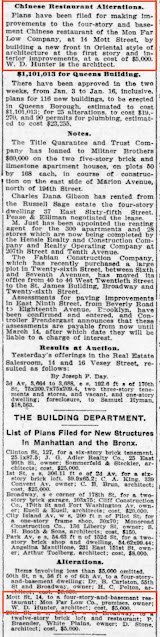

LeasesPlans have been filed for making improvements to the four-story and basement Chinese restaurant of Mon Far Low Company, No. 14 Mott street, by building a new front in Oriental style of architecture at the first story, building a flight of marble steps leading to the entrance and making interior improvements at a cost of $5,000.

The New York Times, January 18, 1911

The Real Estate FieldChinese Restaurant Alterations.Plans have been filed for making improvements to the four-story and basement Chinese restaurant of the Mon Far Low Company, at 14 Mott Street, by building a new front in Oriental style of architecture at the first story and interior improvements, at a cost of $5,000. W. D. Hunter is the architect.Alterations.Mott St, 14, to a four-story-and-basement restaurant; Mon Far Low Co., premises, owner: W. D. Hunter, architect; cost, $5,000.

New York Evening Post, January 31, 1911

‘Charley Boston’ at HomeHis Smile and His Diamonds in Chinatown AgainBail Fixed at $2,500 for Li Quon Jung, the Other Name of the Celestial That Henkel, U. S. Marshal, Arrested for Alleged Complicity in Extended Opium SmugglingAlthough Chinatown was cast into deep gloom yesterday—the second day of its New Year’s celebration—by the arrest of Charley Boston, properly known as Li Quon Jung, it wore an expansive Oriental smile to-day at noon, when Charley returned, still in possession of his diamonds and his modish clothes, after being admitted to $2,500 bail by United States Commissioner Shields, pending examination on February 10 on charge of receiving smuggled opium.Indeed, No. 14 Mott Street, from one of the pagoda-like floors of which above the restaurant of Mon Far Low, Charley Boston emerged last night to fall into the ready arms of Marshal Henkel, was flying a goodly number of green and yellow, dragon bedecked flags, and wore an altogether festive air. ...

New York Herald, October 18, 1911

Chinese Visitors Viewing LibrariesMandarins Are Gathering Ideas for Use in Similar Institutions in Canton.Mr. Quan Kai, special commissioner for the Viceroy of Canton, and Mr. Moy Back Hin, Chinese Consul at Portland, Ore., both of whom are mandarins and philanthropists, are visiting this city. They appeared in Chinatown yesterday and were greeted most cordially by their fellow countrymen. Late in the afternoon the Chinese Merchants’ Association gave a dinner for them in a restaurant at No. 14 Mott street. ...

The New-York Tribune, January 2, 1912, published a photograph of Mott Street.

14 Mott Street, third building from the right

New York Herald, February 9, 1912

Correspondents at Chinatown DinnerWriters for Out of Town Papers Have for Guest F. Augustus Heinze, Who Tells StoriesChinese grand opera on an American made talking machine, Southern melodies by negro minstrels, celestial cocktails and horns browed beer contributed to the success of the eighteenth annual dinner of the New York Correspondents’ Club, given last evening in the Flowery Kingdom Restaurant, No. 14 Mott street. It was the first time the representatives of out of newspapers had their yearly feast in any other than American surroundings.The souvenirs were Oriental caps with long queues that instated on getting in the way of the chopsticks when any one ventured to use those instruments of rapid and free hand eating. There were many dishes which looked the same on the menu card and in real life.F. Augustus Heinze, the copper operator, was a guest and told stories of his career. Among the other guests were Ben Atwell, of the Russian dancers; Winfield R. Sheehan, secretary to Police Commissioner Waldo, Joseph D. O’Brien, of the New York National League Baseball Club, and David M. Shirk, of the Philadelphia Enquirer.

New York Evening Call, November 12, 1912

Chow for Yellow JacketsThe Chinese Merchants’ Association is giving a banquet tonight at 11:45 at the Mon Far Low restaurant on Mott street to the members of “The Yellow Jacket” company, the playwrights and the management. All the Chinese delicacies, from birds’ nest soup to shark’s fins, will be featured.

New-York Tribune, November 12, 1912

Theatrical Notes.The Chinese Merchants’ Association is giving a banquet to-night at 11:45 o’clock at the Mon Far Low restaurant, in Mott street, for the members of the “Yellow Jacket” company, the playwrights and the management.

Mott Street was photographed on January 1, 1913. In the middle of block is 14 Mott Street with a vertical electric sign, flags and rooftop flagpole. Across the street is the Port Arthur electric sign which is partially visible in the upper left corner.

Trow’s Business Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, 1913 listed Mon Far Low.

The International Chinese Business Directory of the World (1913) listed “Mine Far Low, Restaurant” at 14 Mott Street.

The Chinese Students’ Monthly, June 10, 1913

The Edison Monthly, July 1913, printed a photograph of Mott Street. The illuminated vertical sign of 14 Mott Street is on the right.

Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, March 1914 listed Mon Far Low.

The Chinese Students’ Monthly, June 10, 1914

Puck, November 28, 1914. Buildings left to right: 20, 18, 16 and 14 Mott Street

Residents of 14 Mott Street, lines 6 to 11, counted in the 1915 New York State Census.

Trow New York Copartnership and Corporation Directory Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, August 1915 listed Mon Far Low.

Further Reading

Manhattan’s Chinatown (2008)

Related Posts

(Next post on Wednesday: Chu F. Hing’s Painting of ‘Akaka Falls)

No comments:

Post a Comment