A CHRONOLOGY

Formed in 1900, Mann Fong Lowe Company operated the Oriental Restaurant at 3 Pell Street in New York City’s Chinatown.

Illuminated sign, Brown Bros. photograph detail, circa 1900

Date unknown

7.5 x 5.25 inches unfolded

Both businesses were mentioned in The New York Times, January 25, 1902.

The Mann Fong Lowe Company was listed, for the first time, in The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan the Bronx, City of New York, March 1902.

Mann Fong Lowe Co. (R.T.N.) [Registered Trade Name] (Goon Chung & Moy C. Wine [sic]) 3 Pell

George Chung and the Oriental Restaurant were mentioned in the New York Herald, December 14, 1902, section 5, page 11.

... American capital is behind the handsomest and most respectable Chinese restaurant. The Oriental, in Chinatown, is a combination of modern American luxury with Chinese dress. It is managed by an exceedingly clever Chinaman named George Chung. George has been in this country for thirty years and has acquired a thorough knowledge of the American taste and habit. The Oriental is fitted up in a style to please the artistic eye and without regard to expense. It occupies the whole second floor, with its two large connecting dining rooms and pantry. Above are the kitchen and storerooms. The stairway leads to an entrance in the rear of the suite, while the front room opens upon a balcony of wrought iron work overlooking picturesque Pell Street.The two rooms are conventionally separated by an elaborate fretwork screen of colored glass and golden dragons and other Chinese symbols. The floors are covered by tasty patterns of linoleum. The walls are richly decorated with Chinese characters. On one wall is a gorgeous Chinese crest, surmounted by a lovely spread of peacocks’ feathers. It came from China. On either side of the dividing screen facing the door are great Chinese characters running up and down, after the Chinese fashion, from ceiling to floor, signifying “Welcome to visitors.” Half a dozen big Chinese lanterns swing from the ceilings, but the actual lighting is by modern electric lights in beautiful designs.The furniture of the place is of surpassing beauty. It is of massive teak, elaborately carved and profusely inlaid with mother-of-pearl. It consists of a series of small rectangular tables along the walls, with two stools for each, and several round tables in the centre of the rooms for the larger parties. To accommodate more than four an extension wooden cover is laid on one of these round tables or from one square table to another. The stools, like the tables, are heavy, carved and inlaid. This teak wood comes from India and takes on a dull polish like ebony and is as hard as iron. The stools are square.The little cubby with its beautiful screen would fill the soul of the housewife with delight. The screen itself is a rare work of art. And the dishes! The lovely tea cups and bowls and mugs and platters seem too frail and exquisitely designed for anything but ornament. This would be called a pantry in our language. I do not know what the Chinese call it. Its delicate contents rather suggest the treasures of a collector. ...

Four-Track News, June 1903, covered New York’s Chinatown in the article “A Corner of China”. The first photograph was the interior of the Oriental Restaurant.

This photograph is in the collection of the Library of Congress.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, July 1, 1903: “Mann Fong Lowe Co. eatingh [eatinghouse] 3 Pell”.

The New Metropolitan, July 1903, devoted six pages to the Oriental Restaurant.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, August 29, 1903, published a list of Manhattan leases that included

Mott st. No 5, 2d, 3d and 4th floors. Solomon Lent to Mann Fong Lowe Co and Quan Yick Tai Co; 5 years, from Nov 1, 1903. Aug 27, 1903. 1:161.....2,220

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, December 12, 1903, published a list of Manhattan leases that included

Mann Fong Lowe Co and Qua Yick Tai Co with Wm Jay as exr and trustee Isaac Bell, Jr. Mott st. No 5, w s. G4.G n Worth st, No 199. Priority agreement. Nov 30. Dec 7, 1903. 1:161

Illustrations by Hy. Mayer appeared in the 1904 book, The Real New York. Below, the interlocking circular designs (upper left corner) can be seen in previous photographs. In the book, the Chinese Delmonico was visited.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1904, recorded the changes made by the partners.

Mann Fong Lowe Co. (dissolved) 3 PellOriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung & Moy C Winn [sic]) 3 Pell

Entry published in Obsolete American Securities and Corporations, Volume 2, 1911, page 617: “Mann Fong Lowe Co. Office in New York. Dissolved 1904”.

The New York Public Library has an Oriental Restaurant menu dated April 4, 1904.

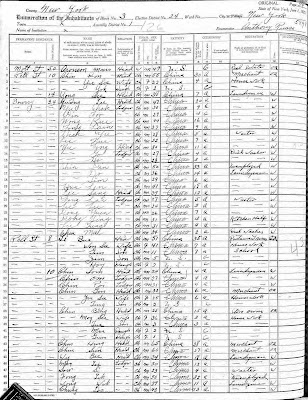

Residents at 3 Pell Street (lines 33–43) in the 1905 New York state census which was enumerated starting June 1. “Li Puie” might be Li Bue.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, July 1, 1905: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, July 2, 1905, published a list of Manhattan leases that included

Pell st, No 3 | or store floor, 3 floors. Ellen Cavanagh EXTRX Wm T McKean to Mann Fong Lowe Co; 5 years, from Feb 1, 1906. June 30, 1904. 1:162.....1,680 and 1,800

New York Herald, December 4, 1905, page 7

Chinese and Japanese Experts Differ on TeaWhether tea is injurious to health is a question over which even Chinese and Japanese authorities are at variance. A reporter for the Herald, who talked yesterday with several of the most prominent Chinese residents of New York learned that there was an equal division between those who declared that tea in practically unlimited quantities may be drunk without any bad effect, provided the beverage is prepared so that the bitter properties of the leaf are not extracted.George Chung, manager of the Oriental restaurant, at No. 3 Pell street, where a majority of the better class Chinese and Japanese of this city drink tea every day, is himself of the opinion that tea should be used in moderation or its toxic properties will soon cause serious nervousness and the physical ailments.“I have used tea,” said Mr. Chung, “all my life, as most of my countrymen use it, and I confess that I have reached a point where I have been forced to limit myself to a few cups each day or I suffer from it. My employees drink great quantities of tea, particularly in the summer, and while few will acknowledge it I have seen its effects in the tremor which attacks their limbs after over-indulgence. This passes away after short time.“Most of the Japanese merchants who come here to dine and drink tea are satisfied with a few cups, but there are a few who use as many as three pots at a meal. Some Japanese bring their own tea to be brewed and insist on its being prepared in a certain way, that is, infused for a certain time, the time being regulated by the taste of the individual for weak or strong tea.“I frequently get an attack of nervousness after drinking four or five cups. This is attended by a headache, which passes off as soon as the nervous tremors abate.”Warren Wong, a Chinese student, who is employed nights in Mr. Chung’s restaurant, said that he drank as many as thirty cups of tea each day during the summer and about fifteen cups a day in the winter.“My people,” said Mr. Wong, “give so little thought to the subject of the possible ill effects of tea that some of them drink literally gallons every day. I drink about thirty cups a day in summer and have never noticed the least bad symptom as a result. I am employed at night and after my duties are over I have frequently consumed three quart pots of tea. I go right to bed and go to sleep almost immediately. During the winter I drink about half as much as in summer. Cold tea which is made by pouring boiling water over the leaves and after it has drawn, as you Americans say, for five minutes, is set in a cool place, is the one liquid used by Chinese laundrymen to allay thirst. I know several Chinese who drink two gallons of cold tea every day, and I never heard them complain of nervousness from its use.”Mr. Wong said that the Japanese who frequent the restaurant would laugh at the idea of any injury to their health being caused by tea drinking. This statement was borne out by several Japanese who dined at the Oriental last evening.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1906: “Oriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung) 3 Pell”.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, July 1, 1907: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1908: “Oriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung & Moy Wing) 3 Pell”.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1909: “Oriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung & May Wing) 3 Pell”.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, May 22, 1909, published a list of Manhattan leases that included

Pell st. No 3 nagh INDIVID and ADMRX Wm T McKean to Mann Fang [sic] Low Co; 5 years, from Feb 1, 1911. May 14, 1909. 1:162 ..... 2,100

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, July 1, 1909: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan the Bronx, City of New York, March 1910: “Oriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung & May Wing & Mon Teug) 3 Pell”.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, August 1, 1911: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan the Bronx, City of New York, March 1912: “Oriental Restaurant (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung, May Wing & Mon Fong) 3 Pell”.

Trow’s General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, August 1, 1912: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”.

Trow’s Business Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, 1913: “Oriental Restaurant, 3 Pell”.

The Trow Copartnership and Corporation Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan the Bronx, City of New York, March 1914: “Mann Fong Lowe Co. (R.T.N.) (Goon Chung, Moy Wing & Mon Fong) 3 Pell”.

Trow’s Business Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, August 1, 1914: “Oriental Restaurant 3 Pell”

R.L. Polk’s 1915 Trow’s New York City Directory, Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1915: “Oriental Restaurant (RTN) (Mann, Fong, Lowe Co) 3 Pell”.

The Photoplayers Weekly, May 21, 1915, “Chinese Actor Entertains Pathe Producers.”

The Wharton’s Taste Bird’s Nest SoupAh Ling Foo, one of the real Chinese actors in Pathe’s “Exploits of Elaine” gave a dinner at the Oriental Restaurant in Pell St., New York, the other night to the Whartons, producers of the “Exploits.” Mrs. Bess Wharton. E. A. MacManus of the Hearst forces, Mr Gordon, assistant to the Whartons, and Mr. and Mrs. J. Whitworth Buck.

Residents at 3 Pell Street (lines 3–19) in the 1915 New York state census which was enumerated starting June 1.

R.L. Polk’s 1915 Trow New York Copartnership and Corporation Directory, Boroughs of Manhattan Bronx,

September 1915: “Oriental Restaurant, Inc (RTN) (Goon Chung, May Wing & Mon Fong) 3 Pell”.

The Harley Spiller Collection includes an Oriental Restaurant menu dated May 3, 1916.

Detail

The New York Times, October 13, 1916, reported the partners’ profit dispute.

Made $20,000 a Year on Chinese VivandsLi Bue, Pell Street Restaurant Treasurer, Must Give Details to Goon Clung [sic].14 Chinese as OwnersBusiness Agreement in 1900 Set Forth That “Today We Have Found a Way to Make Money.”Chinese methods of success in business were revealed in papers filed in the Supreme Court by Goon Clung, formerly manager of the Oriental restaurant at 3 Pell Street, for an accounting of the profits of the place from Li Bue, the Treasurer, who admits that the net profits have been $20,000 annually for the last three years.Goon Clung contends that he was a partner in Mann Fung Low, the Chinese name of the restaurant, and he insists that his rights under an agreement signed on “the Lucky Day in the 26th year of the reign of Kwong Hsu” were not respected when he was removed from the management.Treasurer Li Bue insists that there was no partnership and contends that the agreement under which fourteen Chinamen decided in 1900 to operate the restaurant was that of a voluntary association. He denies that the death of Hor Door, Goon Bum Yen and Lee Ki Non, three of the members, dissolved the partnership and required the distribution of the surplus profits among the members. …

By early 1917, Oriental Restaurant had moved across the street to 4 and 6 Pell Street.

New York Evening Post, February 2, 1917, page six: “Chinese Feast for Reptile-Lovers”

One hundred members, nearly one-half of the number women, of the Reptile Study Society, will attend a Chinese dinner, Monday evening, February 19, at the Oriental Restaurant, 4 Pell Street. The Society aims to teach facts about reptiles and amphibians, and to prove the folly of needless fears of non-poisonous species, and to end the constant cruelty practiced toward harmless crawling creatures.

R.L. Polk’s 1917 Trow’s New York City Directory, Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, March 1917: “Oriental Restaurant, Inc (RTN) (Goon Chung, May Wing, Mon Fong) 6 Pell”.

The Oriental Restaurant’s illuminated sign was featured in The Edison Monthly, July 1917, “Advertising Here and in China”.

The image suffers from a scanning effect

called a moire pattern.

... Passengers by “L” across Chatham Square at night are caught and, optically speaking, held by a veritable orgy of color down the midst of which the letters “ORIENTAL” descend with suggestive Far Eastern twists and turns. If one looks in time these letters flame out again on a second sign from a balcony below. These two up-to-date sign creations are worth stopping to examine.The first is found to rise brilliantly from a no less brilliant cup of tea. This cup of mammoth dimensions is gay with varigated hues accentuated by flashing bulbs in outline. Steam, presumably, that rises from the magical contents vaporizes quickly into the gorgeous shaft of the sign proper. If it were or had ever been possible to describe in English the squirmings and convolutions of Chinese design the same would find place at this point even as the twistings themselves do up the sides and about the top of this oddly lighted shaft. But who can describe them and who can ascribe becoming credit to the sign maker who in this particular case adapted his bulbs and colors to such difficult outlines? But adapted they are, pulsating away with a creepiness that serves to accentuate the wriggles and writhings among which they twinkle. The balcony panel is far less elaborate and contents itself with a transparency effect of darting sun’s rays at the two ends. Yet its letters of the channel type are as quaint as those of the big panel rising above them. ...

Who’s Who of the Chinese in New York (1918), page 89, Restaurants: “Oriental, 4 Pell Street”

R.L. Polk’s 1918–19 Trow New York Copartnership and Corporation Directory, Boroughs of Manhattan Bronx: “Oriental Restaurant, Inc (NY) Li Bue Pres. Hor Door Sec. Louis Fong Treas. Capital $10,600. Directors: Li Bue, Hor Door, Louis Fong. 4 Pell”. (The New York Times’ article, October 13, 1916, said Hor Door was dead.)

The Oriental Restaurant sign appeared in the New York Evening World, August 10, 1922.

The New “Red Book” Information and Guide to New York, Manhattan and the Bronx (1923), page 164: “Oriental, 3 Pell st [sic]”

Rider’s New York City: A Guide-book for Travelers (1923) page 31:

Chinese Restaurants(2) Chinese Quarter (3d Ave. Elevated to Chatham sq., or Interborough Subway to Worth st.) Port Arthur, 9 Mott st.; Oriental, 4 Pell st.; Chinese Delmonico, 24 Pell st.; Suey Jan Low, 16 Mott st.In all these restaurants meals are served both à la carte and table d'hôte, the prices for the latter ranging from 50c

The New “Red Book” Information and Guide to New York, Manhattan and the Bronx (1924–1925), page 165: “Oriental, 3 Pell st [sic]”

The Restaurants of New York (1925), pages 160–161:

Foreign Feeding GroundsOriental. In my search for the most distinctive restaurants in this section I have been guided by one who doubtless knows, Mr. Lee Lock, one of Chinatown’s most respected merchants. His first selection, where I promptly dined, was the Oriental, at 4 Pell Street. It may be accepted as typical of the best Chinatown has to offer. Its white tiled approach is like the entrance to a subway station except that it is immaculately clean and you go up instead of down. A Chinese boy is forever mopping the stairs. The restaurants are always upstairs, the lower spaces being occupied by shops. The rooms have been old hotels or lodging houses in their day. They have no architectural significance, but considerable interest is given them in their accessories and furnishings, carved teakwood tables inlaid with pearl, compartments of red lacquer glazed or decorated with silk-embroidered panels and lanterns with rice paper paintings of ingenious design.The food at the Oriental is very palatable and abounding in surprising combinations, for the Chinese names are obligingly translated on the menu. It varies in price to suit any purse. You may lunch sumptuously on Sub Gum soup, Chowmein, boiled rice and Lychee nuts for thirty-five cents or, if you are dining, you may resort to the à-la-carte features and pay two dollars for the euphonious Bat Bow Foo Yong, which is nothing less than an omelet with chicken, lobster, mushrooms, bamboo shoots and water chestnuts. The names are epic. I long to make repeated visits and try such combinations as Moo Goo Bar Low Guy Pan , which is boneless chicken with pineapple and lots of other things! And there is always the tea. You drink countless cups of it. It goes with the food. There is a harmony in these things which goes deep into the chemistry of food and the mystery of appetite. And, by the way, if you are fussy about your tea you may have any one of a score of brands from the familiar English Breakfast up to the famous Sun Sen Char. It is only fair to warn you that the latter, whose name means “grown on cloud-covered mountain heights,” cost five dollars a bowl. If the tea did not keep you awake, the price might. The proprietor, Mr. Willie Li-Bue, is a gracious and helpful person and his establishment is one to be recommended. He shrugged deprecatingly when he told me that dancing in the evening was to an American orchestra. “They must have,” he said. So has jazz penetrated into the Orient!

Oriental Restaurant sign

Oriental Restaurant sign

Illustration based on photograph; date unknown

The postcard below was available in the late 1940s. (eBay had a postcard with a June 9, 1949 postmark.) It was mailed on August 24, 1952. On the far right, the black Oriental Restaurant sign is below the pink Sugar Bowl sign.

Related Posts

ABOUT GOON CHUNG AND HIS FAMILY

Based on a Chinese Exclusion Act case file interview, Goon Chung aka George Goon Chung said he was born around 1867 in “Hong How village, S.N.D China”. His family name was Goon.

So far, the earliest mention of Goon was in the New York Herald, December 14, 1902.

Goon’s opinion about drinking tea appeared in the New York Herald, December 4, 1905, page 7.

Chinese and Japanese Experts Differ on TeaWhether tea is injurious to health is a question over which even Chinese and Japanese authorities are at variance. A reporter for the Herald, who talked yesterday with several of the most prominent Chinese residents of New York learned that there was an equal division between those who declared that tea in practically unlimited quantities may be drunk without any bad effect, provided the beverage is prepared so that the bitter properties of the leaf are not extracted.George Chung, manager of the Oriental restaurant, at No. 3 Pell street, where a majority of the better class Chinese and Japanese of this city drink tea every day, is himself of the opinion that tea should be used in moderation or its toxic properties will soon cause serious nervousness and the physical ailments.“I have used tea,” said Mr. Chung, “all my life, as most of my countrymen use it, and I confess that I have reached a point where I have been forced to limit myself to a few cups each day or I suffer from it. My employees drink great quantities of tea, particularly in the summer, and while few will acknowledge it I have seen its effects in the tremor which attacks their limbs after over-indulgence. This passes away after short time.“Most of the Japanese merchants who come here to dine and drink tea are satisfied with a few cups, but there are a few who use as many as three pots at a meal. Some Japanese bring their own tea to be brewed and insist on its being prepared in a certain way, that is, infused for a certain time, the time being regulated by the taste of the individual for weak or strong tea.“I frequently get an attack of nervousness after drinking four or five cups. This is attended by a headache, which passes off as soon as the nervous tremors abate.”Warren Wong, a Chinese student, who is employed nights in Mr. Chung’s restaurant, said that he drank as many as thirty cups of tea each day during the summer and about fifteen cups a day in the winter.“My people,” said Mr. Wong, “give so little thought to the subject of the possible ill effects of tea that some of them drink literally gallons every day. I drink about thirty cups a day in summer and have never noticed the least bad symptom as a result. I am employed at night and after my duties are over I have frequently consumed three quart pots of tea. I go right to bed and go to sleep almost immediately. During the winter I drink about half as much as in summer. Cold tea which is made by pouring boiling water over the leaves and after it has drawn, as you Americans say, for five minutes, is set in a cool place, is the one liquid used by Chinese laundrymen to allay thirst. I know several Chinese who drink two gallons of cold tea every day, and I never heard them complain of nervousness from its use.”Mr. Wong said that the Japanese who frequent the restaurant would laugh at the idea of any injury to their health being caused by tea drinking. This statement was borne out by several Japanese who dined at the Oriental last evening.

The Municipal Journal and Engineer, January 6, 1909, printed the following notice.

IncorporationsAmerican Chinese Engineering Company, New York, N.Y.; engineering work in America and China; capital, $100,000. Incorporators: Theodore M. Foote, 253 Putnam avenue, Brooklyn; Frank Lee Lowe, 203 West Twenty-third street; Goon Chung, 3 Pell street, both of New York.

The 1910 United States Census recorded Goon, on line 34, in Manhattan, New York City at 3 Pell Street. He was proprietor of a restaurant.

In 1911 Goon traveled to San Francisco. Marriage license notices appeared in the San Francisco Call and San Francisco Examiner on March 10, 1911.

Chung–Wong–George Goon Chung, 36, New York city, and Florence Lee Wong, 18, 920 Sacramento street.

In June 1911, Goon was arrested for possession of opium. It was reported in many newspapers including the New York Evening World, June 27, 1911; the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 28, 1911; The New York Times, June 28, 1911; and the San Francisco Chronicle, June 28, 1911:

Large Seizure of Opium Made in New YorkDetectives Discover $30,000 Worth of Drug in Home of Chinese Merchant.New York, June 27.—The largest seizure of opium ever made in this city, 355 pounds, valued at $30,000, was made today by central office detectives. The seizure was the result of information received that large quantities of opium were being shipped to Boston and other cities from some man in Chinatown here, and followed the arrest of Goon Chong [sic], of George Chong, manager of an Oriental restaurant on Pell street and owner of grocery stores in Boston and Lynn.Chong came back from San Francisco about two months ago, where he had gone to be married and brought his Chinese wife with him. He lives on the top floor at 195 Worth street, and is known as a successful merchant. Detectives trailed him from his restaurant to his home and to a poultry store at 175 Chambers street, where the Chinese buy their chickens.Today detectives went to the poultry store to investigate. They were told that Chong had left a box there for a short time and that it was supposed to contain crockery. Inside the detectives found 150 pounds of gum opium in the shape in which it is imported from China, wrapped in leaves.While they were looking it over Chong came in and was arrested. Then the detectives went to Ching’s house. His wife opened the door. They told her that Chong was busy and could not get around, but that he had sent them for the opium. Mrs. Chong hauled out from under the bed seventy-five pounds of raw opium, fifty pounds of the cooked product ready for the pipe, and thirty pounds of yen Chee, or opium that has been smoked and is used again.Chong spent the night at police headquarters and will be arraigned tomorrow morning.

The New York Sun, July 22, 1911, said

Made Opium Without Permit.Chung of Pell Street in Trouble With Internal Revenue Men.Goon Chung, or George Chung, as he is better known in Chinatown, where he runs the Oriental Restaurant at 3 Pell street, was arraigned yesterday afternoon before Judge Archbald in the United States Circuit Court on an indictment found by the Federal Grand Jury on July 10. The indictment, charges that Chung unlawfully engaged in the manufacture of opium for smoking purposes without giving a bond as required by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and also that he removed from the place of manufacture for consumption and sale eighty-one pounds of smoking opium which had not been stamped to indicate that the internal revenue tax had been paid.The opium involved in the case is worth about $40,000. Part of it was found in Chung’s rooms on Worth street and the rest in the basement of the Pell street restaurant. Chung was released on $3,000 bail.

The New York Evening World, November 9, 1911, covered the trial.

Chinese Woman a Witness in Her Husband’s TrialMrs. Goon Chung, a petite and sweet-mannered matron of twenty years, was a witness to-day in the United States Circuit Court before Judge Martin in defense of her husband, Goon Chung. Her testimony had apparent effect upon the jury. Mrs. Chung is the first Chinese woman ever to appear on the witness stand in the Federal courts in this city.In their raids upon opium sellers and manufacturers last spring, internal revenue agents descended upon the home of Goon Chung at No. 176 Worth street, and confiscated several boxes of the drug, worth about $3,0OO. They also seized some ashes which they claim are those of opium.The arrest of Goon Chung created not a little excitement in Chinatown. He is one of the big men among the Celestials of the city and many whites whom he numbers among his friends were in court to aid in his defense. Chung is the owner of a restaurant at No. 2 [sic] Pell street. He is interested in the manufacture of a range finder for the government’s warships and in manufacturing brick making machinery to be sent to China. In addition he has a restaurant on Harrison avenue, Boston, and another in Lynn, Mass.The defense is that the opium was placed in Chung’s apartment as a part of a conspiracy arranged for revenge by a Chinese interpreter who had been exposed by Chung.Gives Her Testimony in Perfect English.In perfect English Mrs. Chung told how a man known throughout Chinatown as “Big Lem” came to their home at night while her husband was away and asked if he could leave the boxes for a few days.“My husband is so good and so upright,” she said, “that I could not think any one would want to harm him, and I consented. When my husband came home he said he did not like the looks of the boxes and ordered them taken way and sent to a storehouse. After that “Big Lem” came with some other boxes and wanted to leave them, but my husband would not receive them.”It was while she was a witness that the romance of her marriage was revealed. She was asked how long she had known her husband, and with a smile in his direction, said, “Sincce [sic] last March.” It was in that month that she married Chung. He had gone to San Francisco to visit friends and while in a hotel there met her. A rapid fire courtship ensued. Chung had to returnto New York the following week. He vowed he would not return alone—and he didn’t. While waiting for their apartment to be made ready, they lived at the Waldorf.Mrs. Chung is the daughter of a wealthy Chinese merchant of San Francisco and was educated in girls’ schools in San Francisco and Los Angeles.The trial also developed the fact that the medical societies of this country will not permit Chinese physicians to be licensed and practice. Pak Yam, a venerable and dignified Chinaman from Boston, hesitated when asked his business. Finally he was told it would be necessary to answer, and he said he was a physician.“For more than 1,000 years,” he added, “my people have been physicians in China.”Yam said the ashes the Federal agents found when they raided Chung’s home were those of some herb he had proscribed for medicinal purposes.

Goon’s daughter, Mae Sien, was born on June 2, 1914, in New York City.

The 1915 New York state census counted Goon, his family and relatives in Manhattan at 40 West 126th Street (lines 40–46).

At some point, Goon left the Oriental Restaurant and looked to Brooklyn for a new venture. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 19, 1918, said

New Brooklyn Company.Albany, March 19—With a capital of $55,000, the Picadilly [sic] Restaurant Company, Inc., of Brooklyn, was chartered by the Secretary of State. The directors are George C. Chung, Philip G. Keet and G. Heam of Manhattan.

The Brooklyn Standard Union, August 18, 1918, reported the upcoming opening.

The Piccadilly RestaurantDishes prepared from menus used by the royal families of China and Japan, as well as American dinners, will be served in the new Piccadilly Restaurant, in the old Latimer Building at the junction of Flatbush avenue and Fulton street, when it formally opens to the public on or about Labor Day.At an expense exceeding $50,000 the restaurant officials are renovating the upper floors of the building, which will be used exclusively for restaurant purposes, and where special rooms will be provided for the exclusive use of clubs and sororities and other organizations which might wish to hold banquets and dinners and dances there. The restaurant will be modern in every respect, with all the latest cooking devices, ventilating system, and restaurant settings. Because Chinese dishes will be one of the features of the restaurant the entire place will have an Oriental flavor in the matter of decorations. A firm which is expert in this kind of work is now engaged in transforming the interior and also the exterior to comply with scenes typical of the Orient.Recognizing that the public today likes to be entertained while dining, the management will provide what is termed “Brooklyn’s greatest revue,” named “All Aboard,” which will consist of many singing and dancing and entertaining specialties, and a large chorus of pretty and talented girls with Broadway experience. Victor Hyde, one of the pioneers and leaders in this form of amusement, has been engaged to stage the revue.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

September 15, 1918

The restaurant’s first anniversary was noted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 15, 1919.

Piccadilly CelebratesThe Piccadilly Restaurant, at Flatbush ave. and Nevins st., celebrated its first anniversary last night with a banquet tendered to friends of the management. This is the first time in the history of the restaurant, which has been under three separate managements during the past three years, that one concern, under the direction of Philip Kee, has continued for one year. During the course of the dinner Mr. Kee was presented with a floral horseshoe of flowers, the gift of the employees of the restaurant. Murray Hulbert, Commissioner of Docks and Ferries, was among the guests. Others at the table were Commissioner Hitchcock. Mr. and Mrs. Wiley, Mr. and Mrs. Sison, Miss Selma Shapiro, J. S. Brenner, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kane, Mr. and Mrs. L. A. Grimes and Mr. and Mrs. William G. Hemley. The new revue, entitled “Peacock Alley,” was presented for the first time last night and the restaurant has been entirely redecorated. Kee was formerly in the Government service as a Chinese interpreter and inspector.

Goon has not yet been found in the 1920 census.

The following notice appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 11, 1920.

During Prohibition, the Brooklyn Standard Union, February 14, 1921, said

Prohibition Agents Raid Piccadilly RestaurantFederal Prohibition Agents Edwards, Jacobs and Daly to-day brought Coon [sic] Chung, treasurer of the Piccadilly Restaurant, Fulton street and Flatbush lavenue [sic], and Tse Chung Chi, a waiter, before Federal Commissioner, Rasquin, charged with violating the dry law.The waiter is alleged to have sold a glass of whiskey for $1. The treasurer is charged with maintaining a nuisance. The agents seized a five-gallon copper tank of liquor and two quart bottles. They waived examination for the action of the District Court.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1921, said

New Restaurant Manager.The Piccadilly Restaurant, Flatbush ave. and Fulton st., will open its fourth year Saturday under the new management of George C. Chung.

A headline in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 14, 1923, said “Chung’s $6,700 Goes in “Rolling Store”; Promoter Arrested”.

In the 1925 New York state census, restauranteur Goon and his family were Manhattan residents at 411-409 West 129th Street (lines 20–22).

In 1926, Goon and his family were interviewed in preparation for visiting China. There were no records of their departure or return in the Chinese Exclusion Act case file.

The 1930 census counted the Goon family in Manhattan at 452 or 454 Fort Washington Avenue (lines 94–96). Goon was a restaurant manager.

Daily Argus, (Mount Vernon, New York), March 31, 1933

Woman Motorist, Reckless, Pays $5Tuckahoe, March 31.—Convicted of reckless driving as the result of an accident early this week, Mae Sien Goon, nineteen, 5 Pinehurst Avenue, the Bronx, was fined $5 in Eastchester Court last night by Justice of the Peace Harold F. Gormsen. Emil Slavky, 43 Rose Avenue, Bronxville, Manor, Eastchester, accused the Bronx woman of failing to come to a full stop and cutting him off as she drove out of McKinlay Street to the White Plains Post Road.

Goon and his daughter have not yet been found in the 1940 census. Sometime in the 1930s, Goon’s wife was committed to the Central Islip State Hospital (line 3).

At age 74, Goon passed away on August 1, 1940 in Manhattan. He was laid to rest at Kensico Cemetery. Goon’s death was reported by his daughter.

On June 19, 1943, Mae and Edward Hong obtained a marriage license, in Manhattan. They married the following day. (In the 1940 census, Edward was the restaurant owner of The Mandarin, in Danville, Illinois, which was started by his father who passed away in 1937.)

The couple were Republicans.

In the 1950 census, the couple were counted in Manhattan at 525 East 14th Street, apartment 9H.

Knickerbocker News, May 27, 1955

Binghamton Press, June 24, 1955

Reading Eagle (Pennsylvania), September 3, 1956, Chinese press Agent in Reading for Fair

Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada), July 21, 1961, Unusual press agent job for comely New Yorker

Leader-Post, (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada), July 25, 1961, photograph

Mae passed away on May 4, 1990 in New York City. Newsday, May 8, 1990, published an obituary.

Mae S. Hong, 75, Circus, Theatrical Press AgentNew York—Mae Hong, 75, a press agent whose clients included touring Broadway shows, circuses, carnivals, and the Harlem Globe Trotters, died of cancer Friday at Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan.Mrs. Hong, who lived in Manhattan, was a native New Yorker. She graduated from New York University in 1952 with a degree in journalism and went to work as a public relations representative of the Mills Bros. Circus in Ohio.She then went to the Ringling Bros. and Barnum Bailey Circus and the Clyde Beatty Circus and was one of the first women to work in the traditionally male world of traveling press agents.Among the Broadway productions she represented on road tours were “Carnival”, “My Fair Lady”, “Mame”, “Never Too Late” and “Sweet Charity”.She is survived by her husband Edward. Visiting will be Thursday and Friday 2-5 and 7-9 pm at the Campbell Funeral Chapel, 1076 Madison Ave. Services will be at the chapel 7 pm Friday.

An obituary appeared in The New York Times, May 12, 1990.

Edward passed away on January 31, 2005 in New York.

A FEW DETAILS ABOUT LI BUE

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 10, 1917, page five, “Chinamen Buy Bonds”

Willie Li Bue, vice president of Mun Hey Weekly, a Chinese publication of 16 Pell street, Manhattan, a member of the Chinese National League of New York City, has been taking an active part in the campaign for subscriptions to the Liberty Loan, and has appealed to Brooklyn Chinamen to buy bonds and aid Uncle Sam in crushing Germany. He has contributed $100 personally and $2,000 from his business, the Oriental Restaurant, 4 and 6 Pell street, in the purchase of bonds.This patriotic Chinaman has also purchased many Liberty Loan bonds for Chinese residents of Manhattan and Brooklyn, In an appeal to Brooklyn Chinamen sent out by him today through the Eagle, he says:“In a crisis like the present, we Chinese must do our duty to help our best friend, America. In so doing, every one of us should purchase as many Liberty Loan bonds as we possibly can.”

Warner M. Van Norden, 1918

Page 60

LI BUE—was born in the village of Du Woi, in the district of San Woi, Kwang Tung province in the year 1874. He went to Kwong Moon and followed mercantile pursuits until 1892, when he came to New York. He went to Boston in 1894, under the employ of Wing Sing Lung, and in the interests of the same company, later, took up his abode in Providence, R. I. In 1899 he returned to New York and organized the company now operating the Oriental Restaurant. He is the treasurer and stockholder of a syndicate owning and operating numerous out-of-town restaurants. Address—4 Pell Street.

Li Bue was named next of kin on his brother’s World War I draft card.

American Contractor, December 6, 1919, page 50:

Store & Restaurant (alt.) $40,000, 4 sty. 20–22 Bowery. Archt. Wm. H. Rahman & Sons, 126 Cedar st. Owner Canton Realty Co., Wm. Li Bue, pres., 4–6 Pell st. Brk. Plans drawn.

The 1925 New York state census recorded Li Bue and his family (lines 27–31) at 8 Pell Street in Manhattan, New York City. He was a restaurant owner.

The 1930 United States Census said “Bue William Li” and his family (lines 15–19) were residents at 51 Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown. He was self-employed as an importer and exporter of goods.

“William Li Bue” was named next of kin on his son’s World War II draft card.

(Updated January 11, 2024; next post on Saturday: “The Art of Yun Gee”)

%20p4.jpg)

%20p1.jpg)

%20p9.jpg)

%20p6.jpg)

%20p11.jpg)

%20p.jpg)

%20p12A%20c4.jpg)

%20p17%20c1.jpg)

%20p5.jpg)

%20WWI%20Draft%20Card.jpg)

%20WWII%20Draft%20Card%2001.jpg)

Hi Alex! This post has been an amazing resource for us! We are undergoing renovation to transform the buildings interior (18 Bowery) to resemble its original design as closely as possible. Please email us at edwardmooneyhouse@gmail.com! We'd love to chat more about the buildings history with you.

ReplyDelete