Reprint edition, no date; originally published by Macmillan in 1938

The preface in the 1938 and reprint editions said

... In this book the author has compiled the recipes for Chinese dishes of wide appeal and has also included some of the better chop suey and chow mien recipes. He has had forty years of cooking experience and is considered an authority on real Chinese food.

Evidently, Low started cooking around 1898. On the first page of the reprint edition is a photograph of Low and the phrase “60 Years of Cooking Experience”. Evidently the reprint edition was published around 1958.

Reviews

New York Post, September 20, 1938, page 11

Chinese Dinners at Home.Those who can wind their way in and out of Chinatown and take you to the best twelve-course—or maybe it’s sixteen—Chinese dinner know Henry Low, head chef of the Port Arthur at 7 Mott Street. Now after forty years of Chinese cooking, and Henry Low doesn’t look much older than that himself, we have his favorite recipes, all geared to American markets and kitchens, in “Cook at Home in Chinese,” published today by Macmillan ($2.50).Lin Yutang, who writes the introduction, comments: “Let the meats and vegetables be combined and ‘married,’ instead of meeting each other for the first time when served on the table in their respective confirmed bachelorhood and unspoiled virginity, and you will find that each has a fuller personality than you ever dreamed of.”Mr. Low’s earnings at present go to the relief fund of refugees in China, still another reason for owning this unusual cook book.

Watertown Daily Times (New York), November 7, 1938, page 5

Cook at Home in ChineseProbably enthusiasm for Henry Low’s new book “Cook at Home in Chinese” published by the Macmillan company would be greatly simulated could the chef at the Port Arthur serve the reader such a meal as he recently laid before three epicures from the Macmillan company.Seet Yu Wan Tun, (Snow fungi and Chinese ravioli soup) began it, followed by Hung Yuen Gai Ding (Diced chicken with almonds), Wor Siu Op (Brown stewed duck with chopped almonds), Mr. Low’s own recipe Tchun Guen. Foo Bok Gop (Chinese fried squab; Chow Loong Ha (Lobster Cantonese style) with tea. Bamboo sprouts went into these dishes, gourmet powder and rice wine.But as the title of the new book suggests you can cook Chinese food with its help in your own home and the result will be that since such food is more carefully prepared than American you can eat more of it. For instance Mr. Low uses Chinese water chestnut flour which makes a deviously flavored flaky covering for the egg rolls known in Chinese as Tchun Guen. So successful has Tchun Guen proved that now nearly all Chinese restaurants serve some sort of Tchun Guen.At the Port Arthur classical Cantonese cooking has prevailed, and thus far the war in China has not interfered with the Post Arthur supplies. Other people, too, can purchase them at herbalists on Pell street and at almost any Chinese vegetable shop on Mott. The oyster sauce, for instance, does not need to be restricted to Chinese dishes but this mouth watering condiment may be added to the butter melted on steaks or chops.

Richmond Times-Dispatch (Virginia), December 4, 1938, page 13

Mr. Low Cooks in ChineseHenry Low, who has been chef at the Port Arthur—one of New York’s best known restaurants—for the past 10 years, is polite but unenthusiastic about American cookery. You can eat a lot more Chinese food and not know it, he says. This is because it’s more carefully prepared. Mr. Low’s new book of Chinese recipes has just been published by the Macmillan Company under the title of “Cook at Home in Chinese.”He considers that his principal contribution to Chinese cookery is a new sort of Egg Roll called Tchun Guen. He discovered about 30 years ago that by using Chinese water-chestnut flour he could make a deliciously-flavored flaky covering for the rolls, more palatable than the ordinary dough used by his rivals. This innovation has found favor with gourmets everywhere. Nearly all Chinese restaurants now serve some sort of Tchun Guen. But in general Mr. Low feels it’s better not to experiment; the classical Cantonese cuisine reigns at the Port Arthur.Mr. Low says the war in China hasn’t interfered so far with the Port Arthur’s supplies. Though prices have gone up (some of the rarer ingredients cost $5 or more an ounce) they are still being exported safely through Hong Kong and he has no fear of a famine in New York’s Chinatown.Three epicures from The Macmillan Company visited the Port Arthur and Mr. Low gave them a delicious Chinese dinner, consisting of Seet Yu Wan Tun, (Snow Fungi and Chinese Ravioli Soup); Hung Yuen Gai Ding (Diced chicken with almonds); Wor Siu Op (Brown stewed duck with chopped almonds); Mr. Low’s Tchun Guen; Foo Bok Gop (Chinese fried squab); Chow Loong Ha (Lobster Cantonese style), and of course tea and more tea. The ingredients of these dishes ranged from bamboo sprouts to gourmet powder and rice wine. The result was a delectable meal, and the guests went home fired with ambition to “Cook at Home in Chinese,” especially as the recipes for all these delicacies are included in Mr. Low’s book.

ABOUT HENRY LOW

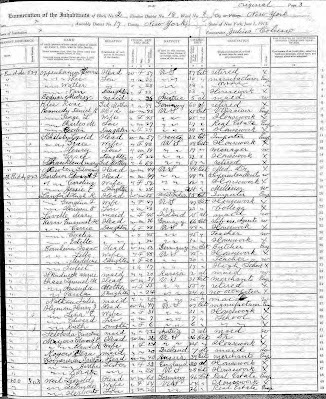

Little is known about Henry Low. In the 1900 United States Census, there was a Henry Low born in May 1855 in China. He immigrated in 1875. When he arrived in New York is unknown. The census recorded him and his Caucasian wife, Jennie, in Chinatown at 20 Bayard Street. His occupation was chef. (See line 21)

The 1910 census had a Henry Low born around 1878 in China. He immigrated in 1879 and resided in Chinatown at 65 Mott Street. He cooked for a family.

On September 12, 1918, another Henry Low, born February 13, 1879, signed his World War I draft card. He lived at 45 Mott Street and was a cook at the Bun Hurn Restaurant. The restaurant menu is here.

A Henry Low restaurant employee, in New York City, has not yet been found in the 1920 census.

In the 1930 census, a California-born Henry Low was 37 years old. He lived at 62 Essex Street near Chinatown. He cooked at a restaurant. (See line 41)

Low was at Port Arthur Restaurant when this postcard was postmarked on November 6, 1933.

A Henry Low restaurant employee, in New York City, has not yet been found in the 1940 census. The New York Times, April 30, 1940, said

Two Restaurants Lease in MidtownRiker Chain and Henry Low Sign for Eating Places in West 49th StreetAmong the commercial rentals reported by brokers yesterday were two restaurant leases in West Forty-ninth Street, between Sixth and Seventh Avenues.… Henry Low, Chinese restauranteur and author, took a store in the building at 131–35 West Forty-ninth Street, which is being remodeled by Benjamin Winter. Mr. Low was for ten years head chef of the Port Arthur Restaurant, and last year published “Cook at Home in Chinese.” He will open a Chinese restaurant in the newly-rented space in June. …

Cookbook author Henry Low spent time in San Francisco where he was the chef at Canton Low in Chinatown.

San Francisco Chronicle, November 1, 1940

On April 27, 1942, a Henry Low signed his World War II draft card. He was born in April 26, 1886 in San Francisco. His address was 28 Massachusetts Avenue NW, in Washington, DC. He worked at the Chinese Lantern Restaurant.

The cookbook author Henry Low was associated with the Good Earth Restaurant, in Washington, DC, as seen in the following advertisements.

In 1947 the New York Post printed China Doll advertisements that mentioned cookbook author Henry Low.

April 29, 1947

July 24, 1947

July 31, 1947

The Library of Congress has an August 21, 1949 dated photograph of Pell Street in New York City. There was a Henry Low Restaurant at number 24 where the Chinese Delmonico once operated.

A Henry Low restaurant employee, in New York City, was in the 1950 census. Born in California, he was 64 years old and lived at 746 Ninth Avenue. He was the proprietor of a restaurant (see line 26).

In the New York Post, November 29, 1956, Dining Out Tonight guide, the Chinese-American category mentioned, for the first time, Low at Ho Sai Guy restaurant.

Finest Chinese-American Cuisine. Personally cooked by Henry Low, famous author of “Cook at Home in Chinese”—Family dinners, superb American foods. 223 W. 80 St. nr. B’way. TR 4-8296.

The New York Post, April 2, 1957, talked to Henry Chen of Ho Sai Guy Restaurant.

... Owner-host Henry Chen told us proudly of his chef, Henry Low, author of the book, “Cook at Home in Chinese,” with its foreword by philosopher Lin Yutang. Then we sampled some of Low’s handiwork, and we’re convinced. ...... Chen mentioned that chef Low, who has worked in many of the city’s best places in the past 45 years, has been credited by some with popularizing such favorites as egg roll, dem sen, sub gum chow mein and wor shu duck. That distinction is claimed by many others, but it’s enough to know that the food is good, served hot and is sensibly priced. ...

The review said Low worked at various restaurants for 45 years (started around 1912). The preface in “Cook at Home” in Chinese said Low had cooked for forty years (started around 1898). In 1957, the ages of the various Henry Lows, based on the census and draft card dates, are as follows:

102, 1900 census

79, 1910 census

78, World War I draft card

64, 1930 census

71, World War II draft card

70, 1950 census

The Henry Low in the 1900 census is too old and the one in 1930 too young. It’s a toss up among the Henry Lows in their 70s. The date and place of Henry Low’s passing is unknown.

Related Posts

SIDEBAR: Grace S.R. Hillyer, Writer and Designer

Opposite the preface was an acknowledgement.

The author desires to acknowledge his sincere debt of gratitude to Grace S. R. Hillyer without whose friendly and invaluable assistance in editing and arranging these recipes and preparing the manuscript this book could not have been written.

How and when Henry Low met Hillyer is not known. Hillyer may have been an editor or an assistant at the publisher Macmillan.

Grace S.R. Hillyer was born Grace Schilsky on August 7, 1892 in New Rochelle, New York, according to a birth record at Ancestry.com. In the 1900 United States Census, Hillyer, her younger brother, Henry, and parents, Leo and Grace, lived at 39 Bay View Avenue in New Rochelle. Her father, a French-native, was an importer. (See lines 40 to 43.)

In the 1910 census, their address was 57 Woodland Avenue in New Rochelle (lines 28 to 31).

The 1915 New York state census recorded the Schilsky family (lines 11 to 14) in New York City at 829 West End Avenue.

Their residence in the 1920 census was 231 West 96 Street (lines 34 to 37). The census said Hillyer was an art student.

According to the 1930 census, Hillyer was a widow (line 96). At the time her married name was Ridenour. Details of her marriage have not been found. Hillyer, her mother and an uncle, also widows, lived in Maurice River, New Jersey. Hillyer’s occupation was illegible on the census sheet.

During the war between China and Japan, Americans were providing aid to China. Hillyer was involved with the American Bureau for Medical Aid to China. Her letter was published in The Christian Leader, August 12, 1939.

In the 1940 census, Hillyer had remarried to William H. Hillyer, a factor in finance. She was a freelance designer (line 62). Also living with them was her mother. They lived in Manhattan on Lexington Avenue near East 28th Street.

Her letter was published in the New York newspaper, PM, December 26, 1941.

Dear Editor:I have satisfactorily solved my blackoutproblem without spending any money and would like to pass the idea along to your readers.I have equipped the wrong side of my scatter rugs with drapery rings, sewn on to leave upper half of rings free, and placed about two inches from one end of each rug. These rings are not in the way and are not marring my polished floors. I have placed screw hooks at the tops of my window frames in such a way as to enable me to hang the rugs on them. The rugs being somewhat heavy, they may be pressed against the windows so that not a ray of light can escape. Where the rugs are not large enough they may be lapped and pinned with heavy safety pins. Table oil-cloth, if of a dark color, is often opaque, and may be easily handled if equipped with rings and hung from screw hooks.

She was thanked in her husband’s book, Keys to Business Cash: A Guide to Methods of New Financing (1942).

Hillyer’s “Chinatown New Year” was published in Westminster Magazine, Winter 1949–1950.

High heels click-tapping with weight of tray burdensPunctuate pauses in Cantonese gossip;And quick cleaver blows staccato from kitchenResharpen the rhythm of phonograph love-song:Falsetto, ear-thrilling.Three voices dispute split of gee foa winnings;Additional tones swell the theme of new choices.A door-slam proclaims the collection of money.Two choruses foretell two gambles as certain:“Elephant—Dead Man!”“The crash of a bottle is greeted with laughterWhile child-squeal is smothered by murmurous pity.A wine-gladdened toast hails Triumphant Republic—Is answered by banqueters’ New Year’s greeting:“Goong hai, fat choy!”

The 1950 census recorded Hillyer and her husband in Manhattan at 332–340 East 84th Street in apartment 2A. She was a self-employed writer and designer (line 30).

Hillyer was mentioned in The Office, March 1953.

The New York Times, October 27, 1959, published her husband’s obituary. He had three daughters from a previous marriage.

The Social Security Death Index said Hillyer passed away in November 1977. Her last residence was New York City.

SIDEBAR: Leja Gorska, Dust Jacket Designer

Leja Gorska was born Leandra Podgorsek on June 22, 1897, in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. The birth name was on her marriage certificate and birthplace on a passenger card. Gorska immigrated around 1910.

On December 30, 1921, Gorska married Nickolas Muray in Manhattan, New York City.

Their daughter, Arija, was born on August 11, 1922 in New York City.

The 1925 New York state census listed Gorska (line 34) as unmarried and a resident at 428 Lafayette Street in New York City. She was a dancer who was in the United States for 15 years.

According to Billboard , May 29, 1926, Gorska danced in the film “The Rainmaker”.

On September 23, 1928, Gorska and her daughter (lines 11 and 12) departed Havre, France and arrived in New York City on October 1.

According to the 1930 census, Gorska was divorced and a self-employed artist. She and her sister (lines 10 and 11) lived at 428 Lafayette Street in Manhattan. Their immigration date was 1913

The Tenth Annual of Advertising Art (1931) featured art by Gorska.

Gorska designed the dust jacket for “The Quiet Shore” which was published by Macmillan in 1937. In 1938 Macmillan published Henry Low’s “Cook at Home in Chinese” with a dust jacket by Gorska.

On October 15, 1939, Gorska and her daughter (lines 2 and 3) returned from a visit in Europe.

Gorska and her daughter (lines 6 and 7) were counted in the 1940 census. They lived at 124 Waverly Place in Manhattan. Gorska was a painter.

Gorska learned photography from her former husband. Advertising Age, February 10, 1941, said

Leja Gorska and Dushan Hill have formed Gorska-Hill, with offices at 52 W. 52nd street, New York, taking over the photographic studio formerly headed by Ben Pinchot at the same address.

Gorska’s portraits appeared in many books and magazines.

Gorska’s daughter passed away September 19, 1941.

Gorska was not found in the 1950 census. A passenger list said she returned from France on October 2, 1950 (see line 25).

Two months later, Gorska departed on December 7, 1950 to live permanently in France.

She visited New York in 1958.

Gorska passed away on October 29, 1988, in Bordeaux, France, according to the Social Security Death Index.

Further Reading

Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, August 13, 1940

Who Was Who in American Art 1564–1975 Volume II: G–O

(Next post on Wednesday: Flower Drum Song, November 1960–April 1961)

%20p7.jpg)

%20p11.jpg)

%20pB13.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment